Learning a foreign language is not nuclear science even though people who are nuclear scientists (and have enormously high IQs) may struggle with it as the “g factor” is not an exact science. The beautiful English language is one of the easiest tongues to learn. And luckily it is lingua franca. But is there any tricky part? Yes, it is called “articles”. At least when your native language is a Slavic one (even though you are a genetic mix of everything).

How tricky is it to learn a foreign language

Linguistic distance refers to how different the new language is from your native language. Languages that are more similar to your native language are generally easier to learn. For example, a Spanish speaker may find it easier to learn Italian than Japanese due to the similarities in vocabulary, grammar, and syntax between Spanish and Italian.

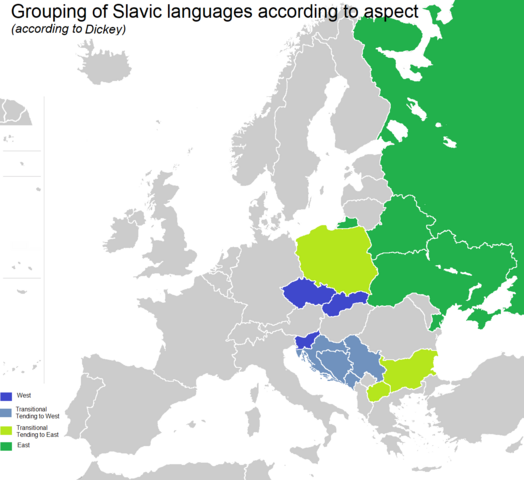

So as a Czech native speaker, my close languages are Slavic: Russian, Polish (some Czechs can understand it), Slovenian, and so on.

Older learners may find it more challenging to pick up new languages due to reduced neural plasticity.

Staying motivated and consistent in practice can be difficult over time. Also, languages like Finnish or Turkish use agglutination. They combine many morphemes in a single word, which can be complex to learn.

When learning a language from your teenage years, you won’t (maybe with some exceptions) acquire the proper accent.

Learning a new script or writing system adds another layer of complexity. For example, learning to read and write in Mandarin Chinese, with its thousands of characters, is more challenging than learning a language that uses the Latin alphabet.

How tricky is it to learn articles for a Czech speaker

Learning a foreign language that uses articles (such as “the,” “a,” and “an” in English) can indeed be tricky if Czech does not use them. This difficulty stems from the need to understand not only the concept of articles but also their correct usage in various contexts.

For example, “a cat” vs. “the cat.” This concept might be entirely new and abstract for Czech language speakers.

Understanding the difference between definite articles (specifying something known or specific) and indefinite articles (referring to something general or not previously mentioned) can be confusing.

Learning when to use definite articles versus indefinite articles involves understanding specificity and context. It can be nuanced and full of exceptions.

However, unlike any other Slavic language, the Czech language overuses demonstrative pronouns because Prague was full of German-speaking people back then influencing the Czech language (and Czech had influenced Czech German which Germans and Jews have spoken). So Czechs are better on than Russians, Poles, and so on). And Prague had been influencing the Czech and Slovak languages for centuries.

Am I going to screw it up forever?

The answer is simple and it is “yes”! We have “the president of the US”, “a president of the US”, and “president of the US. Highly suspicious for me!

I have also seen “Israel” and “an Israel” which led me to even greater confusion.

If there is anything I am best at, it is pervering the beautiful Shakespearian language. Wait? “A, the or nothing”. Who cares?

Leave a Reply