Nationalism brought nothing but gas chambers and we should get rid of it. Maybe I do look like a Czech, have Czech DNA, but I couldn’t care less. I don’t care whether you are white, black, South Asian, East Asian. I assess a person by his intelligence, talents, creativity, personality and moral values. However, despite awful Hitlerian attempts to connect skull and facial features to the “values” of an individual, I am deeply convinced we shouldn’t be repulsed by studying the DNA and – I am convinced – we shouldn’t be repulsed recognizing nationalities better by faces than DNA as for now (in 2024).

I started to reinvent the wheel

While strolling the streets of the Czech Republic (hopefully, this will be part of one global government one day – without nationalism), I was always assessing: “This man looks like a German! This man looks like a Pole!”

Since I didn’t know anything, I was wrong all the time. They say the German and Czech populations are genetically overlapping. When I was hit with the first knowledge (Germans have high and prominent cheekbones, a triangular face that is broad in average of height), I was stunned and claimed you could recognize a German and Czech with 95 % probability.

But I had the chance to browse a book about painting and there were tons of markers that make not only nations different, but also individuals.

Recognize nationalities better by faces than DNA: painters’ knowledge

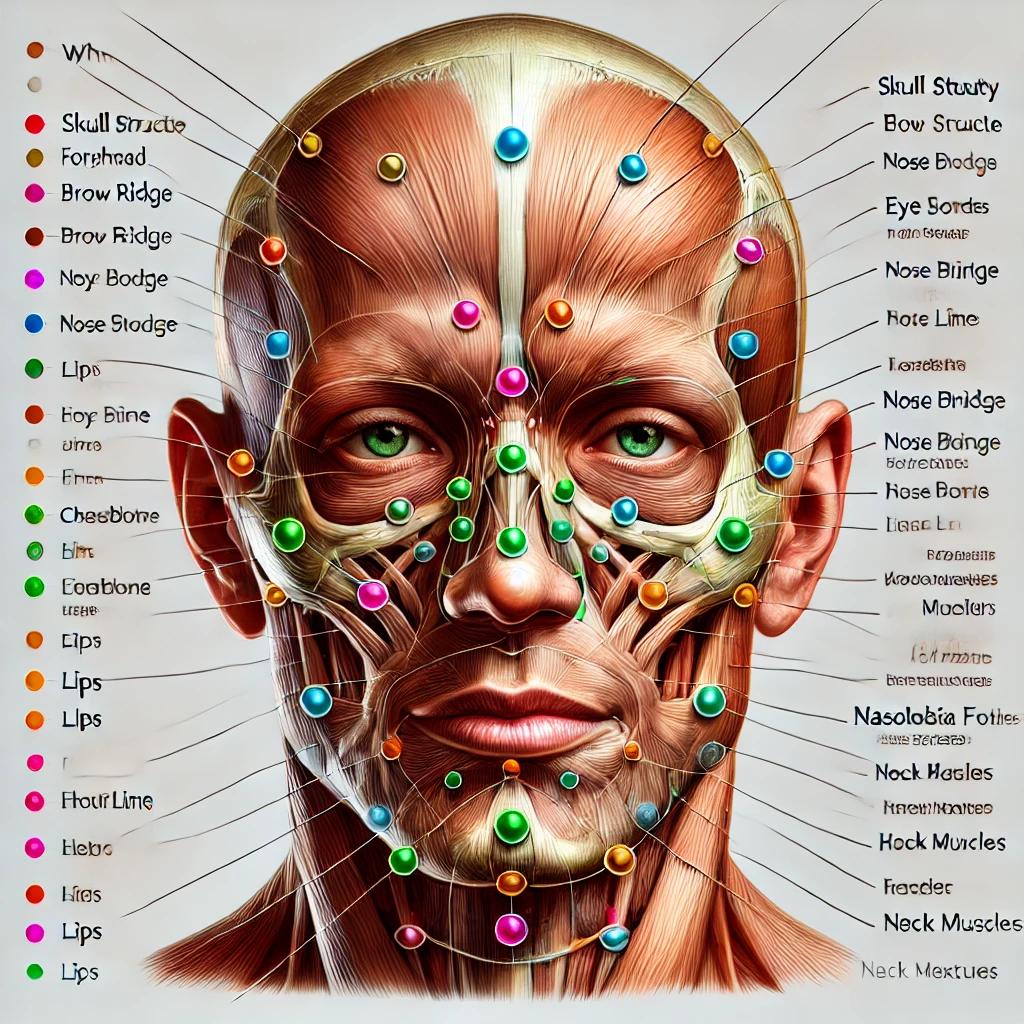

When professional painters approach a face, they delve deeply into the many anatomical and structural details that make each person unique. These features, often subtle yet distinct. They reflect not only individual identity but also the physical traits linked to different European nations. Centuries of geographic, cultural, and genetic evolution have shaped these variations, and painters must understand them to create authentic portraits.

The process begins with the skull structure, the foundation of any face. In northern Europe, skulls often have a more elongated shape, giving the face an angular look. In contrast, southern Europeans might have more rounded skulls, contributing to softer facial contours. This fundamental difference is critical for painters, as it affects how light and shadow play across the face. The forehead, which is often broader in northern European populations, can appear more pronounced. While in southern Europe, a lower and less angular forehead contributes to a more balanced, oval shape.

Eyes

The brow ridge and eye sockets are next. In northern and eastern Europe, the brow ridge can be more defined, giving the face a more intense or sculpted look. Deep-set eyes, often associated with eastern European populations, add to this effect, making the gaze appear more piercing. The eye sockets in Mediterranean populations are less deep, leading to softer expressions. For painters, these subtle shifts in depth and shape define how they approach the placement of the eyes and the overall mood conveyed through the portrait.

The nose is another central feature that varies between regions. Northern European noses are often straighter and narrower, while in southern Europe, a slightly curved or more prominent nose is common. In eastern Europe, noses can be more varied, sometimes with a more pronounced bridge. Painters must capture these nuances because the nose plays a key role in defining the face’s balance and harmony. A nose that aligns perfectly with the cheekbones and jawline enhances the subject’s national and individual identity.

Cheekbones

Cheekbones are among the most distinctive features across different populations. In Scandinavia and central Europe, high, prominent cheekbones often stand out, giving the face a sharper, more angular look. In contrast, southern Europeans may have lower, softer cheekbones, which contribute to the rounder facial shape often associated with the Mediterranean. These differences are subtle but essential for painters, as the cheekbones create the volume of the face and determine how light interacts with the skin.

The zygomatic arch, the bone that connects the cheekbone to the jaw, also varies across populations. In northern Europe, a more pronounced arch can create a wider, more defined look. In southern Europe, this arch may be less prominent, creating a smoother transition from the cheek to the jawline. Painters must understand how this structural element affects the side view of the face, especially when working with shadows and highlights to create depth and realism.

Jawlines

Jawlines also differ significantly between European regions. In northern and eastern Europe, a strong, angular jawline is often common. This can give the face a more chiseled, defined look, which painters capture to emphasize strength or determination. In southern Europe, the jawline may be softer, less pronounced, which adds to the overall roundness of the face. For painters, capturing this difference is crucial, as the jawline frames the lower part of the face and plays a major role in its overall balance.

Moving down to the chin, the shape varies depending on regional traits. A prominent chin is often seen in northern European faces. Whereas in southern Europe, a softer, more rounded chin can be more common. This subtlety influences how painters finish the lower face, affecting the proportions of the portrait as a whole. The philtrum, the small groove between the nose and the upper lip, though often overlooked, must be carefully depicted. Its shape and depth vary from individual to individual. But it also reflects subtle cultural differences, with some populations showing a more pronounced philtrum than others.

Lips

The lips are a major focus for painters. Northern Europeans may have thinner lips, which add to the angularity of the face, while fuller lips are more common in southern Europe, contributing to a sense of warmth and softness. Painters pay special attention to the cupid’s bow, the contour of the upper lip, as it is key in capturing the subtleties of a person’s expression. The lips are also framed by nasolabial folds, the smile lines that run from the sides of the nose to the mouth. These lines can be more pronounced with age and are essential for adding character and personality to a portrait.

The neck muscles, particularly the sternocleidomastoid and the platysma, create the connection between the head and the body. In some regions, necks may appear longer or shorter, depending on the subject’s ancestry. Painters often include these muscles to ensure that the head appears naturally supported, adding to the overall realism of the portrait.

Ears

Ears, though not always the first feature to stand out, provide balance and proportion to the face. Painters must capture their size and placement accurately, as they vary widely across individuals. Hairlines, too, are key. A higher hairline can give the face a longer appearance. While a lower hairline can soften the upper part of the face, especially in combination with the forehead’s shape. These features subtly contribute to the distinctiveness of different European nations.

Eyebrows and eyelids further define the face. In northern Europe, eyebrows may be lighter and more angular. While in southern Europe, they are often darker and more curved. Eyelids also vary, with deeper-set eyes more common in eastern Europe, contributing to a more dramatic gaze. Painters need to pay attention to these details, as the eyes are often the focal point of any portrait. The color of the iris and pupils also reflects regional variation, with lighter eyes more frequent in northern Europe and darker eyes more common in southern regions.

Skin tones

Skin tones are perhaps one of the most visible markers of regional diversity. In northern Europe, skin tends to be fair, often with pinkish undertones, while in southern Europe, warmer, olive tones dominate. Painters must master the play of light and shadow on different skin tones to create depth and realism. The texture of the skin, whether smooth or more textured with age, also plays a role in how the face is depicted.

Finally, light and shadow interact differently with each of these features, depending on the face’s structure. Painters must study how light falls on the brow ridge, nose, and cheekbones, creating highlights and shadows that bring the portrait to life. This interplay of light and anatomy reflects not only the individual’s personality but also the broader traits of the nation or region they represent.

The faces that painters depict carry the history of centuries, shaped by migration, climate, and culture. The differences between nations, though subtle, are embedded in these facial markers. While nationalism may not appeal, the distinct traits across European populations tell a story of diversity and identity that painters bring to life on the canvas. Each face, with its unique combination of features, becomes a testament to the rich cultural heritage of Europe.

Recognize nationalities better by faces than DNA: our DNA knowledge is limited

They tell us we can barely tell the difference between Austrians and Czechs in terms of the DNA. The same goes with Hungarians, Poles and Germans. We can distinguish them better by just a glance than complicated DNA tests.

Czechs, Poles, Germans and Austrians each share certain regional traits but also have distinct physical features shaped by their geographic and cultural histories. These differences, though subtle, are noticeable when you pay attention to the facial structures that painters or observers might focus on, such as the skull shape, cheekbones, eyes, and overall face proportions.

Without a doubt., recognizing nationalities is better by faces than DNA.

Czechs

Czechs often exhibit a blend of central European traits. The skull structure is typically oval, with faces tending toward softer contours rather than sharp angles. Their cheekbones are generally moderate, not as high or sharply defined as seen in some eastern European populations, but still giving structure to the face. The forehead is often broader and gently sloped.

Eyes are typically almond-shaped, with a neutral set that doesn’t sit too deep but also doesn’t protrude. The nose tends to be straight or slightly rounded at the tip, without pronounced curves. Lips are of moderate fullness, with the lower lip often slightly more prominent than the upper. Skin tones in the Czech population tend to be fair, often with a pinkish or light beige undertone, especially among northern Czechs. Hair and eye colors range widely but commonly include medium brown or light brown hair, and eye colors may range from blue to light brown.

Poles

Poles, particularly those from the northern and central regions, often display features associated with Slavic populations, but with variations due to their country’s diverse geography. The skull shape is generally more angular, with sharper lines, particularly around the jawline and chin. High cheekbones are common, adding a more sculpted look to the face, and they are often more pronounced than those of Czechs.

The brow ridge may also be more defined, giving a slight intensity to the eyes. Polish noses can vary, but a slightly hooked or arched nose bridge is seen more often than in the Czech population. Eyes tend to be deep-set, with darker shades of brown, hazel, or green being more common, though light-colored eyes, especially in the north, are also frequent. Lips are usually moderately full, with a more pronounced cupid’s bow, adding expressiveness to the mouth. The skin tone in Poland can range from fair to light olive, with many individuals displaying light complexions but with slightly more olive or yellowish undertones compared to Czechs. Hair colors range from dark blonde to deep brown, with some lighter tones, particularly in the north.

Austrians

Austrians typically exhibit features reflecting their position at the crossroads of central and southern Europe. The face shape is often oval or slightly longer, with softer angles than what you’d see in eastern European populations, but still more defined than in many southern Europeans. The cheekbones in Austrians tend to be moderate to high, giving some structure to the face without being overly sharp or angular.

The forehead is usually broad, with a gently sloping profile, and the jawline is softer compared to Poles, but more defined than Czechs. Austrian noses are often straight or slightly aquiline, with a more prominent bridge than is typical in Czechs. Eyes are generally almond-shaped and may range in color from light brown to green, blue, or grey, with lighter shades more common in the Alpine regions. Lips tend to be more neutral in fullness, with a balanced upper and lower lip, contributing to a more reserved, classical facial appearance. The skin tone of Austrians is generally fair to light, sometimes with a slightly ruddy complexion in the Alpine areas. Hair color is often medium brown to dark blonde, with lighter hair and eye colors being more frequent in the mountain regions, influenced by northern European traits.

Germans

Germans typically have a mix of northern and central European traits. The skull shape is often broad and slightly elongated, giving the face a structured look. The forehead is usually wide, with a straight or gently sloping brow ridge, which adds to the sense of strength in the upper part of the face. Cheekbones in Germans are high and sharp.

The nose in Germans tends to be straight and of medium length, though there is variation. Some have a more aquiline or slightly curved nose, especially in regions closer to southern Europe. The nose bridge is usually well-defined, but not as pronounced as in some Slavic or Mediterranean populations. The jawline in Germans is often strong and angular, with a pronounced chin, especially in northern regions. This gives the lower part of the face a balanced, square appearance, which is common in many central European populations.

Eye shapes

Eye shapes are typically almond, with a neutral set that doesn’t sit too deep nor protrude, giving a calm, neutral expression. Their color in Germans varies widely, but lighter shades, such as blue, grey, and green, are common, especially in northern Germany. In southern regions, brown or hazel eyes are more frequently seen, reflecting the influence of central European genetic traits. The eyebrows are often thick and straight, complementing the wide forehead and giving the face a defined, structured appearance.

Lips in Germans are generally moderate in fullness, with a balanced upper and lower lip. The cupid’s bow is usually subtle, contributing to a more reserved, classical expression. The overall facial proportions in Germans lean towards symmetry and balance, with no single feature dominating the face, which reflects a sense of strength and neutrality.

Skin tones in Germany range from fair to light, often with a slight rosy undertone in northern regions, while in southern areas, the skin may show more beige or olive hues due to the influence of central Europe. Hair colors in Germans range from dark blonde to medium brown, with lighter shades being more common in the north and darker tones appearing more frequently in the south.

These regional traits, shaped by centuries of migration and cultural exchange, make the German population visually distinct yet connected to the broader European landscape. Painters and observers can note the balance and symmetry in German faces, the strong jawlines, and the variety in eye and hair colors, reflecting the country’s central position in Europe geographically.

Recognizing nationalities better by faces than DNA: We are still bad at measuring it

The discovery of DNA was groundbreaking, revolutionizing science by revealing the genetic code that defines all living organisms. And it can now pinpoint which population you are from by analyzing specific genetic markers inherited from your ancestors, tracing geographic origins and ancestral migrations with remarkable accuracy.

However, it is still not so precise. We can pinpoint your origin from the skull or face. Of course, DNA plays a significant role, but you can tell the difference between a Czech, German or Austrian.

Conclusion: be scientific but get rid of nationalism

Political correctness shouldn’t limit us in scientific inquiry. However, nationalism, which is an artificially invented phenomenon, should cease to exist. Nations—artificially invented to some degree—should be considered as entities with specific DNA and appearances.

Even though I am deeply connected to the Czech gene pool and couldn’t have been created from others, I have no pride in this “gene pool.” I am not a nationalist or patriot.

Once again, nationalism brought nothing but gas chambers, but scientific exploration shouldn’t be limited.

Leave a Reply