Sigmund Freud shaped psychiatry more than any other figure. His influence was enormous, yet it crippled the field for decades. Psychiatry, which should have been rooted in science, instead became a speculative mess. Freud’s ideas dominated despite their lack of evidence. His followers built a dogma around him. Critics were ignored, and alternative approaches struggled to gain traction. Even today, many psychiatric elites refuse to acknowledge the damage. They pretend Freud was merely a phase in psychiatry’s evolution. However, they avoid admitting that his dominance set the field back for years.

Freud’s work did not just slow scientific progress. More importantly, it harmed real patients. Psychoanalysis convinced the world that talking endlessly about childhood trauma was the key to treating mental illness. As a result, patients with schizophrenia or severe depression were left without real solutions. Instead of medical interventions, they were forced into fruitless conversations about repressed memories. This approach, unchallenged for decades, discredited psychiatry in the eyes of medicine. Neuroscience and pharmacology could have advanced faster if not for Freud’s grip on the profession.

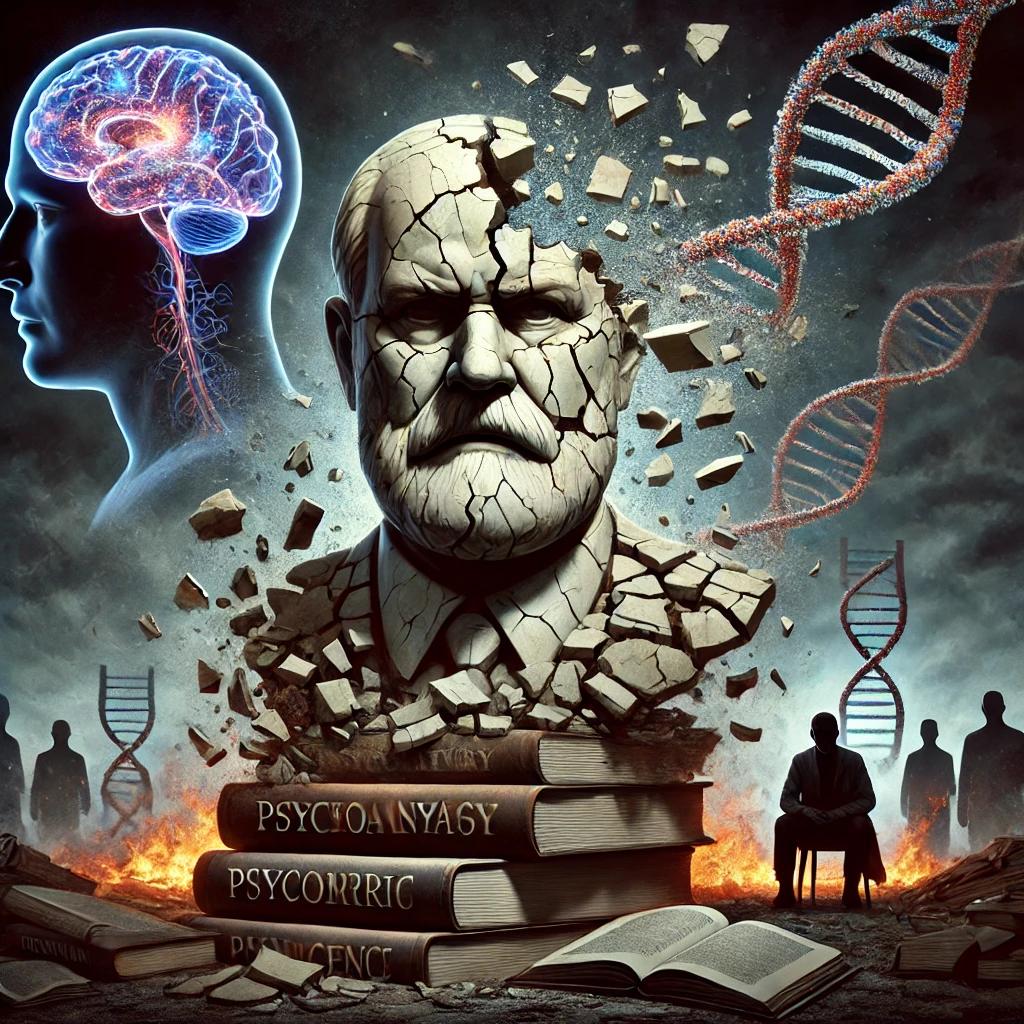

Sigmund Freud: Decieving all of his life

Freud’s entire career was built on deception. He was not just wrong—he was a fraud, manipulated case studies, fabricated results, and convinced patients that they suffered from non-existent conditions. He was a self-proclaimed conquistador (“I am by temperament nothing but a conquistador—an adventurer, if you want it translated—with all the curiosity, daring, and tenacity characteristic of a man of this sort.”), an adventurer who prioritized grandiose theories over truth. In reality, he was a criminal. He knowingly deceived his patients and the medical establishment, and he did so for personal fame and financial gain. His followers, the so-called psychiatric elites, became his accomplices. They helped sustain his fraudulent empire, profiting from unscientific methods while real psychiatric patients suffered.

Sigmund Freud knew his ideas were controversial. As he once remarked, “In the Middle Ages, I would have been burned alive. Now they are content with burning my books.” When the Nazis burned his works in 1933, his books were destroyed, but his influence endured. Ironically, while his theories were rejected by fascists, they were still embraced by the psychiatric establishment.

Today, Sigmund Freud is no longer the dominant force he once was. In some ways, his reputation has faded. Yet his influence lingers. Many therapists still use psychoanalytic methods, often without admitting it. Popular psychology is filled with his ideas. The belief that childhood trauma shapes adult dysfunction comes straight from Freud. The obsession with hidden, unconscious motives in human behavior is another relic of his theories. Though psychoanalysis is not mainstream psychiatry anymore, its core values remain embedded in how people think about the mind.

What is psychoanalysis?

Psychoanalysis is Sigmund Freud’s creation. It claims the unconscious mind is the key to human behavior. It argues that suppressed childhood experiences shape personality. Furthermore, it sees repressed desires as the source of neurosis. Freud believed mental illness came from unresolved psychological conflicts, not from the brain itself. His method of treatment was simple: make the patient talk.

Patients lay on a couch, free-associating thoughts. Freud interpreted their words, dreams, and mannerisms. He saw symbolism in everything. If a patient forgot a name, it meant something. Or if they dreamed about climbing a staircase, it was a sexual metaphor. If they resisted his conclusions, it was “denial.” No matter what the patient said or did, Freud always found a way to confirm his theories. He never considered that he might be wrong.

Freud’s idea of repression shaped the entire field. He believed traumatic memories were buried in the unconscious mind, causing mental illness. This concept was widely accepted for decades, even though there was no evidence for it. However, research now shows that traumatic memories are often remembered too well, not repressed. Freud’s theory led to decades of misguided therapy, where patients were encouraged to “recover” memories that never existed. This created false memories and hysteria, particularly in cases of supposed childhood abuse.

Additionally, psychoanalysis ignored medical science. It disregarded the role of genetics, neurochemistry, and brain disorders. Freud treated psychiatric conditions like they were stories to be decoded. He did not believe in biological explanations for mental illness. This rejection of science held psychiatry back for decades.

Criticism: The dumb psychiatric elites and their reluctance to reject Freud

Sigmund Freud’s theories should have been discarded quickly. Yet the psychiatric establishment embraced them. Many of the field’s top figures built their careers on psychoanalysis. Because they had too much invested to admit it was wrong, they resisted change. They dismissed critics.

For decades, Freud’s theories controlled academia. Professors built their reputations on Freudian analysis. Journals refused to publish studies that contradicted psychoanalysis. They forced medical students learn his ideas as if they were scientific fact. Consequently, the psychiatric establishment turned Freud into an untouchable figure.

Karl Kraus saw through the charade. He described psychoanalysis as a closed system, impervious to criticism. It was self-referential nonsense, explained nothing. It predicted nothing. Yet psychiatrists treated it like holy doctrine.

Even as new evidence exposed Freud’s flaws, many resisted change. In the 20th century, Richard Webster exposed Freud’s deceptions in Why Freud Was Wrong. He showed how Freud manipulated data and misrepresented cases. Frederick Crews went even further, dismantling Freud’s entire legacy. Nevertheless, mainstream psychiatry hesitated to fully reject Freud. Too many careers depended on keeping his ideas alive.

Examples of academic dishonesty

His case studies, rather than being objective analyses, were shaped to fit his preconceived notions, often disregarding contradictory evidence and alternative explanations.

The case of “Dora” (Ida Bauer) exemplifies this. Dora rejected Freud’s analysis of her supposed repressed desires, but instead of revising his theory, he framed her rejection as further proof of repression. Similarly, in the case of the “Wolf Man,” Freud retrofitted childhood memories to reinforce his Oedipus complex theory, ignoring contradictions and alternative psychological factors that may have contributed to the patient’s condition.

Freud also exaggerated the success of psychoanalysis, omitting failed cases or reinterpreting them as incomplete rather than acknowledging limitations. In the case of Sergei Pankejeff, known as the “Wolf Man,” Freud claimed to have cured him, yet Pankejeff later stated that he continued to struggle with his condition, directly contradicting Freud’s claims.

His cocaine research followed a similar pattern. Freud promoted the drug as a medical wonder, ignoring mounting evidence of addiction and harmful effects. Even as reports surfaced about its dangers, he persisted in advocating its use, demonstrating a disregard for scientific integrity.

Additionally, Freud borrowed ideas from thinkers like Schopenhauer and Nietzsche without proper acknowledgment, repackaging existing philosophical concepts as his own groundbreaking psychological discoveries. His relentless need to validate his theories at all costs overshadowed objectivity, distorting the credibility of psychoanalysis and raising lasting questions about his academic integrity.

Psychiatry: The slow recovery from Freud’s damage (1950s–present)

Freud’s dominance lasted far too long. His fraud infected psychiatry for nearly a century. The process of moving psychiatry toward a scientific foundation began in the 1950s with the introduction of psychopharmacology. The discovery of chlorpromazine (Thorazine) in 1952 revolutionized the treatment of schizophrenia. Furthermore, the rise of lithium treatment for bipolar disorder in the 1960s further eroded psychoanalysis. It became clear that mood disorders had biological underpinnings.

By the 1970s and 1980s, psychoanalysis was losing credibility. The DSM-III (1980) abandoned Freudian classifications and introduced a symptom-based approach. Additionally, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) emerged as an evidence-based alternative. Unlike psychoanalysis, CBT produced measurable improvements in treating depression and anxiety.

In the 1990s, neuroscience took over. Brain imaging techniques like fMRI and PET scans provided direct evidence of brain abnormalities in psychiatric disorders. The DSM-IV (1994) and DSM-5 (2013) removed nearly all traces of psychoanalytic terminology. Consequently, psychiatry now focused on biological, cognitive, and behavioral models of mental illness.

By the 2010s, psychiatry was firmly rooted in neuroscience. Genetic research identified specific risk factors for mental illness, such as the DISC1 gene for schizophrenia and the SERT gene for depression. Neurotransmitter dysfunction is widely accepted as a key factor in psychiatric disorders. Additionally, evidence-based therapies like CBT, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and medication dominate clinical practice.

Despite all this progress, some therapists still practice psychoanalysis, especially in Europe and the United States. The idea that childhood trauma explains all adult dysfunction remains common in self-help culture. Concepts like the “inner child,” “repressed trauma,” and “subconscious desires” are Freudian remnants, still influencing how people discuss mental health.

Even with the overwhelming evidence against it, psychoanalysis refuses to die completely. However, its role in psychiatry is now marginal. Freud’s empire has crumbled, and modern psychiatry is still recovering from the damage.

Conclusion: Sigmund Freud and destruction of psychiatry

Freud was not just a fraud. He was a criminal. He knowingly deceived his patients and the psychiatric establishment. If Sigmund Freud had committed his crimes physically (for example, breking legs of 10 000 thousands of people (and we are living in a moral system very close to moral nihilism)), he would have been hanged if the death penalty were present. His so-called theories ruined psychiatry for decades. Furthermore, he and his followers denied patients real treatment, causing unnecessary suffering.

His legacy was not just a mistake—it was a crime against science. Psychiatry has come a long way, but Freud’s shadow still lingers. Therefore, the field must remain vigilant. Pseudoscience has no place in mental health. Freud’s influence must be completely eradicated for psychiatry to move forward.

Still wondering why exact sciences ridicule humanities? Tens of years of Freud’s speculative theories and manipulated case studies, a stark contrast to the era’s advancements in physics with the confirmation of quantum electrodynamics and the discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation, in chemistry with the rise of polymer science and the development of recombinant DNA technology, and in medicine with the widespread adoption of MRI technology and the first artificial heart implants. The stagnation of psychoanalysis, a glaring failure amid revolutionary strides in computing with the rise of personal computers and the development of microprocessors, in engineering with the expansion of space exploration through the Voyager missions and the Space Shuttle program, in telecommunications with the spread of mobile phones and fiber optic communication, and in transportation with the emergence of high-speed rail systems and the Concorde’s supersonic passenger flights.

Leave a Reply