Colonialism was one of the most brutal and exploitative systems in human history. It stripped entire continents of their resources, destroyed cultures. And subjugated millions for the economic and political gain of a few imperial powers. At its core, colonialism was not about civilization but domination—violent, systematic, and unapologetic. It imposed foreign values, dismantled indigenous governance, and created lasting inequalities that persist today. For all its claims of “progress” or “development,” colonialism left behind fractured societies, stolen wealth, and legacies of oppression. Colonialism and religion is are subjects of mutually intertwined and complex relationships.

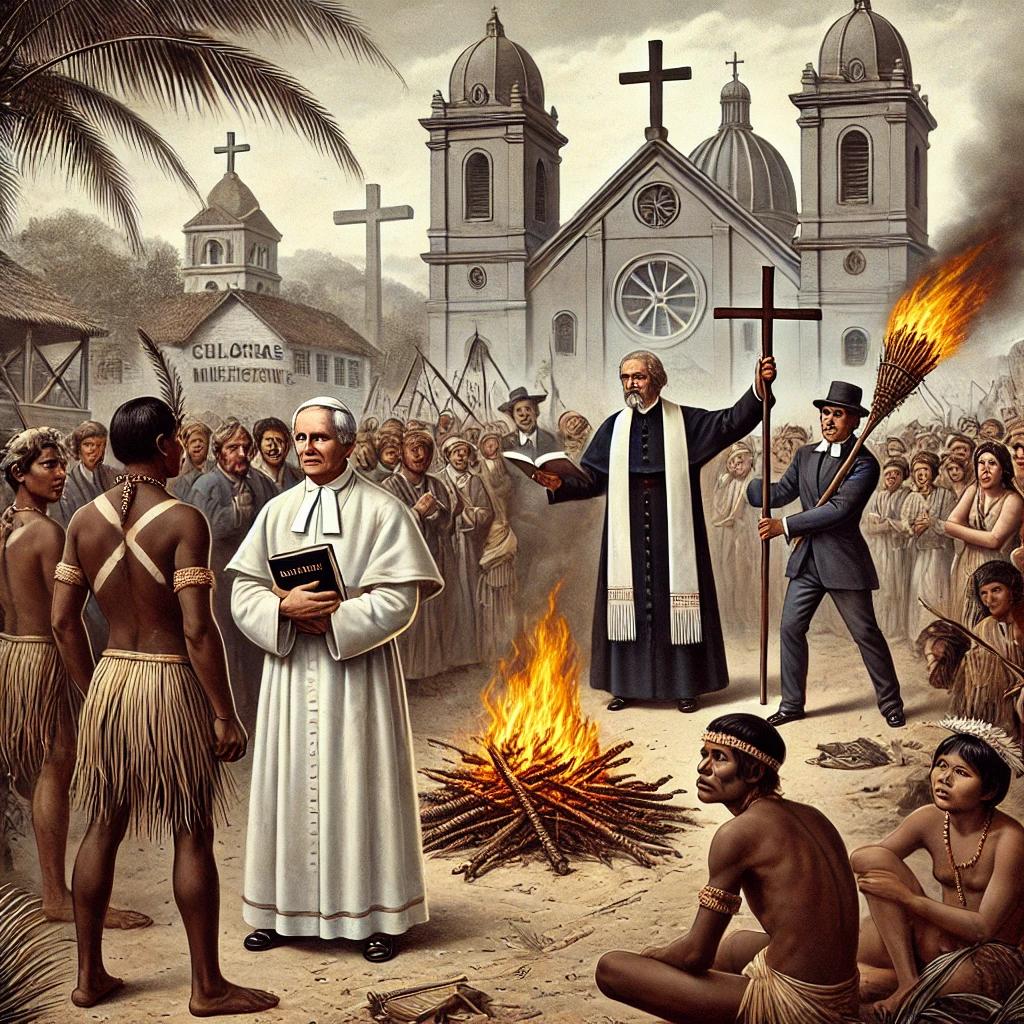

Religion played a dual role in this system. On one hand, it served as a justification for conquest, with missionaries framing their efforts as a moral obligation to “save” indigenous populations. Religious institutions aligned with colonial powers, often facilitating the erasure of local beliefs and imposing foreign spiritual hierarchies. On the other hand, religion became a form of resistance. Colonized peoples adapted and transformed the religions imposed on them, using faith as a tool for survival and rebellion. This duality highlights the complex and often contradictory role religion played in the colonial project.

Artificial borders as a disregard for race, religion and ethnicity

Colonialism’s disregard for existing social, cultural, and ethnic landscapes caused long-term devastation. Artificial borders, drawn by imperial powers in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, split cohesive communities. It also forced rival groups into unnatural unions. These divisions sowed the seeds for civil wars, ethnic violence, and religious strife that still haunt these regions today. The colonizers treated people as commodities, ignoring their histories and identities. They reduced vibrant, complex societies to manageable units of exploitation. This fueled inter-group tensions that erupted into bloodshed once colonial rule ended.

Religion was wielded as both a justification and a weapon. Colonial powers claimed moral superiority, presenting conquest as a divine mission to civilize the “savages.” Missionaries followed the armies, not with guns but with Bibles. Yet their work often had the same result: the suppression of indigenous cultures. Local religious practices were condemned as barbaric, sacred sites were destroyed, and entire populations were coerced into abandoning their spiritual identities. Colonial religion was not about faith. It was about control. It erased diversity and replaced it with obedience to the empire’s moral framework, laying a spiritual foundation for the subjugation of millions.

Colonialism and religion: Nothing but instability

The artificial borders imposed by colonial powers have caused lasting instability, leading to ethnic, religious, and territorial conflicts that persist today. In Africa, colonial borders ignored tribal and ethnic divisions, forcing rival groups into the same states while splitting cohesive communities across multiple nations. This was a key factor in the Rwandan Genocide. Colonial favoritism toward the Tutsi minority over the Hutu majority created deep resentment that erupted into mass violence. Similarly, in the Middle East, the Sykes-Picot Agreement carved the region into arbitrary zones of European control. This disregarded religious and ethnic complexities. This division set the stage for enduring conflicts like the Israeli-Palestinian crisis, where competing claims over land, fueled by religious and historical narratives, remain unresolved. These borders, drawn without regard for local realities, have sown distrust, fostered competition for resources, and made peaceful coexistence difficult, leaving a legacy of division and conflict.

Nothing but exploitation

Colonialism thrived on ruthless exploitation. Entire populations were enslaved or forced into labor. Many were taxed into poverty to serve the economic ambitions of imperial powers. Natural resources such as gold, diamonds, and spices were stripped away. These were funneled into Europe’s wealth, leaving colonized nations impoverished. Industries were deliberately stifled. Colonizers prevented local economic development to maintain dependency on the imperial center. Education, healthcare, and infrastructure were designed only for the colonial elite. The majority was left with nothing but backbreaking labor and systemic oppression.

Without colonialism, many regions could have followed different paths. Africa, for example, might have developed its own trade networks and governance systems. This could have fostered internal growth and unity. Instead, it was left fractured and conflict-ridden. Indigenous civilizations in the Americas could have continued advancing in science, agriculture, and architecture. They were interrupted by conquest and genocide. The Middle East, free from arbitrary borders, might have remained cohesive and stable. It could have built on its rich history of scholarship and trade.

Colonialism did not bring progress. It stole it. Natural development was derailed and replaced with systems designed to benefit foreign powers. The claim that colonized nations needed colonialism to develop is false. These societies could have thrived independently, preserving their identities and strengths.

Disruption of traditional governance

Artificial borders imposed by colonial powers dismantled traditional systems of governance, replacing them with centralized states that ignored local political structures. Pre-colonial systems, often based on tribal, clan, or ethnic leadership, were adapted to the needs and realities of the people they served. These structures were swept aside in favor of foreign administrative models that centralized power in capital cities, leaving rural and local communities disconnected from decision-making. For example, in Somalia, clan-based governance systems, which had maintained balance and social cohesion, were replaced by a centralized state that struggled to enforce authority across diverse clans. This led to internal divisions, weakening the state’s legitimacy and stability. The imposition of foreign governance systems left post-colonial states ill-equipped to navigate internal diversity, fueling cycles of instability and conflict.

Imported religion

Colonial powers imposed their religions to control and reshape colonized societies. Missionaries aggressively spread Christianity, framing it as superior to local spiritual traditions. They destroyed sacred sites, banned indigenous practices, and labeled native beliefs as “barbaric.” Colonizers used religion to justify their dominance, claiming they were bringing “civilization” to the conquered peoples.

Religious conversion disrupted existing cultural structures. Indigenous leaders often derived authority from spiritual traditions. By replacing these systems with imported religions, colonizers weakened local power dynamics and consolidated control. New religious hierarchies elevated converts loyal to the colonial regime, further fragmenting communities.

Education systems based on imported religion replaced traditional knowledge with colonial ideologies. Mission schools indoctrinated children, teaching them to reject their heritage and embrace foreign values. Over time, these systems eroded indigenous identities and created a population alienated from its cultural roots.

Imported religion also redefined morality and social norms. It often introduced rigid structures of sin and salvation, replacing flexible, community-based ethics. Practices like polygamy, gender roles, and community rituals were demonized or outlawed. The colonizers reshaped societies according to their own moral frameworks, leaving lasting scars on social and cultural life.

While some used imported religion as a tool for resistance and adaptation, its introduction irreversibly altered colonized societies. The spiritual and cultural transformation it caused left communities divided and disconnected from their histories.

Catholicism vs Protestantism abroad

Protestants and Catholics competed fiercely during colonial expansion. Both wanted to spread their faith and gain influence. In the Americas, Catholic Spain and Portugal dominated early colonization. Their missionaries sought to convert indigenous populations. They built churches, established missions, and erased local spiritual practices. Protestant nations like England and the Netherlands soon followed. They worked to undermine Catholic influence while spreading their own religious ideologies.

This competition extended to Africa. Catholic powers like France and Belgium sent missionaries deep into the continent. They aimed to establish dominance through religion. Protestant nations, especially Britain and Germany, countered with their own missions. They built schools, translated the Bible into local languages, and emphasized education.

Religious rivalry created deep divisions. Converts aligned with different colonial powers. This fractured communities and disrupted traditional structures. Both sides justified their actions as moral, claiming they brought salvation. In reality, their efforts fueled cultural destruction and heightened colonial exploitation. This struggle for religious control reshaped societies, leaving lasting divisions across the Americas and Africa.

Religion and gender roles

Colonialism and imported religion profoundly redefined gender roles. This has often marginalized women and introducing stricter patriarchal norms than those found in indigenous societies. Many pre-colonial cultures had more fluid and balanced gender dynamics, with women holding significant roles in governance, trade, and spiritual leadership. For example, in parts of Africa, women acted as community leaders, traders, and even warriors, while in indigenous American societies, women often played vital roles in agriculture, decision-making, and religious ceremonies.

Colonial powers, however, imposed rigid gender hierarchies based on European models. These prioritized male authority in both public and private spheres. Missionaries reinforced these norms, framing women’s roles as submissive and domestic, tied to ideals of Christian morality. Education for girls, if provided at all, focused on household skills and obedience, limiting opportunities for leadership or independence.

Imported religions also reshaped legal and cultural frameworks, reducing women’s rights. For instance, colonial legal systems often replaced indigenous practices that allowed for female landownership or divorce with patriarchal laws that stripped women of these rights. In South Asia, British colonial rule codified practices like purdah (female seclusion). And solidified oppressive structures like the caste system, further restricting women’s mobility and agency.

These changes not only marginalized women but also erased their historical contributions, leaving lasting legacies of inequality. The imposition of foreign religious and cultural norms transformed women’s roles into more subordinate positions, entrenching patriarchal systems that persist in many post-colonial societies today.

Resistance

Resistance to colonialism often arose from the same forces that colonial powers sought to suppress: culture, religion, and community identity. Across colonized regions, groups used both armed struggle and spiritual resilience to fight imperial domination. These movements were not just political or military. They were cultural battles to preserve ways of life, languages, and belief systems.

In Africa, resistance groups often drew strength from indigenous spiritual practices. Leaders like Nehanda Charwe Nyakasikana in Zimbabwe invoked ancestral spirits to inspire rebellion against British rule. In Kenya, the Mau Mau movement combined traditional Kikuyu beliefs with modern tactics, turning religion into a unifying force. These groups did not just fight for independence. They fought to preserve cultural identity against forced conversions and the erasure of their heritage.

In Latin America, indigenous communities resisted through both revolt and adaptation. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 in modern-day New Mexico was a rare success. Indigenous leaders expelled Spanish colonizers for over a decade, reclaiming their lands and spiritual practices. Over time, movements like the Zapatistas in Mexico blended indigenous values with modern revolutionary ideals, using their cultural roots as a foundation for resistance.

Middle East and Southeast Asia resistance

In the Middle East, resistance often centered on religion. Islamic leaders like Abdelkader in Algeria and Omar Mukhtar in Libya used faith to rally people against European invaders. These movements framed their struggles as jihad, not just against military occupation but also against the cultural imposition of foreign powers. Faith became both a weapon and a shield, preserving identity while resisting conquest.

Southeast Asia saw similar patterns. The Aceh War in Indonesia pitted local Muslim leaders against Dutch colonial forces. Islamic networks provided both logistical support and ideological strength. Meanwhile, Buddhist monks in Burma (now Myanmar) resisted British rule, combining nonviolent defiance with spiritual leadership. These movements reinforced the importance of religion and local culture as tools of resistance.

These groups were not isolated. They were deeply tied to their communities, drawing strength from shared histories and beliefs. Their resistance was not just about politics or territory. It was about survival—cultural, spiritual, and communal. They showed that even under the crushing weight of colonial oppression, people could fight to preserve their identities and ways of life.

No exploitation: Africa without colonialism in the 21st century

Without colonialism, Africa in the 21st century would likely have followed a vastly different path. Many regions would have developed their own political systems, trade networks, and economies, tailored to local needs and cultures. African empires, such as the Mali Empire, the Kingdom of Kongo, and Great Zimbabwe, might have continued to thrive. This would have expanded their influence and built connections with global markets on their own terms.

Natural resources would have remained in African hands, potentially creating wealth that could be reinvested into infrastructure, education, and local industries. Without the exploitation and extraction by colonial powers, economic growth might have been more evenly distributed across the continent. Trade with Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, rather than being coerced, could have remained voluntary and mutually beneficial, fostering innovation and cultural exchange.

Colonialism and religion: Cultures and languages would have remained intact

Cultural and linguistic diversity would have remained intact, avoiding the erasure and homogenization imposed by colonial rule. Indigenous knowledge systems and practices could have evolved alongside global advancements, creating unique contributions to science, medicine, and governance. Religious syncretism might have occurred naturally, rather than being enforced by missionaries, allowing for a more organic blending of spiritual traditions.

Without artificial borders imposed by colonial powers, many of the ethnic and regional conflicts that plague Africa today might have been avoided. Nations could have formed along cultural and linguistic lines, creating more stable and cohesive societies. The absence of colonial favoritism and divide-and-rule tactics might have reduced internal divisions and allowed for stronger cooperation among African states.

While no path is free of challenges, Africa without colonialism might have been a continent of self-determined progress. Its rich resources and diverse cultures could have formed the foundation for a network of powerful, interconnected nations, contributing to global innovation while preserving its unique identity.

Without colonialism, Africa’s indigenous spiritual traditions would have evolved naturally, coexisting with Islam and Christianity in ways that respected cultural identities. The absence of forced conversions and religious competition imposed by colonial powers could have fostered harmony, reducing tensions and preserving Africa’s spiritual diversity.

The Middle East and Latin America without colonialism in the 21st century

Without colonialism, the Middle East in the 21st century might have been vastly different. The region could have retained its historic role as a global hub of trade, culture, and scholarship, building on its legacy as the center of the Silk Road and the cradle of ancient civilizations. Free from the artificial borders imposed by colonial agreements like the Sykes-Picot Treaty, nations might have formed more naturally along ethnic, linguistic, and religious lines. This would have reduced the sectarian and ethnic tensions that plague the region today. Regional powers such as the Ottoman Empire or the Safavid Empire might have transitioned into modern states with self-determined governance, avoiding the fragmentation and instability caused by foreign interference.

What to exploit: Oil wealth

The region’s oil wealth, which became a focal point for colonial exploitation, could have been harnessed by local governments to fund regional growth and infrastructure rather than enriching foreign corporations. Advanced education systems, strong institutions, and homegrown industries could have emerged, allowing the Middle East to play a leading role in global innovation and diplomacy. Religious diversity, while still complex, might have been less politicized without the divide-and-rule tactics employed by colonial powers. Communities could have focused on coexistence and mutual respect, rooted in their shared histories rather than in externally imposed divisions.

Latin America, without colonialism, might have seen the flourishing of its indigenous civilizations, such as the Aztec, Maya, and Inca. These societies, which already had sophisticated systems of governance, agriculture, and trade, could have continued to innovate and expand, forming powerful and interconnected nations. By the 21st century, these civilizations might have evolved into advanced, unified states, each with unique cultural identities but connected through trade (their own super-rich groups) and diplomacy. The natural resources of the region—such as silver, gold, fertile lands, and biodiversity—would likely have remained in local hands, used to benefit local economies rather than being extracted to enrich European empires.

Complete erasure

The cultural and linguistic erasure imposed by European colonizers might never have occurred. This would have allowed indigenous languages, traditions, and belief systems to dominate. A unique blend of innovation and tradition could have emerged, reflecting the diverse strengths of the region’s people. Instead of struggling with the entrenched inequality and exploitation left by colonial systems, Latin America could have built equitable societies that prioritized education, healthcare, and technological development. The region might have played a more prominent role in global affairs, contributing to scientific advancements, trade networks, and cultural exchange on its own terms.

Without the systemic exploitation and destruction caused by colonialism, both the Middle East and Latin America could have entered the 21st century as powerful, self-sufficient regions. Their unique identities and histories might have shaped a world where diverse cultures thrived, contributing to the progress and richness of human civilization.

Religion without colonialism

Without colonialism, religion in the colonized world would have evolved along its own paths, shaped by local cultures, histories, and societal needs. In the 21st century, indigenous spiritual systems would likely remain dominant, deeply tied to the identity of each region. These systems, often tied to the land, seasons, and community values, would have continued to adapt and evolve without the disruption of forced conversion and cultural suppression. Religion would be less homogenous, reflecting the diversity of human experience rather than the imposed frameworks of imperial powers.

In Africa, traditional spiritual systems would likely still hold a central place in people’s lives. Religions focused on ancestral worship, nature spirits, and community rituals would have continued to thrive. Islam, which entered parts of Africa through trade centuries before colonialism, would still have expanded naturally, growing alongside indigenous beliefs rather than replacing them. Christianity, already present in Ethiopia and parts of North Africa long before European colonization, might have spread more gradually. This would have blended with local traditions rather than erasing them. Religious practices would likely vary widely across regions, shaped by unique cultural identities and local innovations. Without the competition and divisiveness introduced by missionary efforts, African societies might have experienced more religious harmony, using spirituality to unify rather than divide.

The Americas

In the Americas, the Aztec, Inca, and Mayan civilizations, along with countless other indigenous groups, would have maintained their complex religious systems. These systems, often tied to astronomy, agriculture, and communal rituals, would have evolved to address modern challenges. For example, the emphasis on environmental balance in many indigenous religions might have played a central role in contemporary approaches to climate change and conservation. Christianity, brought initially by explorers and settlers, could still have found a place. But its spread would have been voluntary and more limited. Syncretism would have emerged organically, blending indigenous and foreign beliefs without the violent imposition of one over the other. Sacred sites like Machu Picchu or Teotihuacan would still serve as spiritual centers, untouched by colonial destruction.

In the Middle East, Islam would remain dominant, but its development might have been less influenced by colonial manipulation. Without foreign interference, religious reforms could have occurred naturally, driven by local scholars and communities. Christianity, deeply rooted in the region since its beginnings, might have maintained a stronger presence in areas like Egypt, Syria, and Iraq, coexisting peacefully with Islam. Jewish communities, too, might have flourished without the displacement and upheaval caused by colonialism and later geopolitics. Religious diversity, a hallmark of the region before colonialism, could have been preserved, with less politicization of faith and fewer externally imposed conflicts.

South and Southeast Asia

In South and Southeast Asia, Hinduism, Buddhism, and indigenous animistic traditions would likely still dominate. Without colonial suppression, local religious practices might have remained vibrant and more closely tied to community life. The caste system in India, while a deeply entrenched social hierarchy, might have evolved differently without British exploitation. This often reinforced and institutionalized it for administrative purposes. Islam, which had already spread widely through trade and cultural exchange, would have continued to grow in harmony with other faiths, contributing to the rich tapestry of spiritual life in the region. Colonial-era missionary efforts to convert populations to Christianity would have been minimal, leaving indigenous traditions largely intact.

The Pacific islands, home to a variety of animistic and nature-based religions, would have retained their spiritual practices, deeply tied to the ocean, land, and ancestral lineage. These traditions, focused on balance and respect for nature, might have gained global recognition as sustainable and holistic approaches to life. Without the dominance of Christianity imposed by European settlers, these beliefs could have flourished into the modern era. Thus, remaining central to cultural identity and governance.

Overall, religion in a world untouched by colonialism would reflect the natural evolution of diverse spiritual systems. Faith would likely remain deeply local, adapted to the specific needs, environments, and values of each society. While globalization might still introduce cross-cultural exchanges of ideas and practices, these interactions would occur on equal terms rather than under the shadow of coercion. Indigenous religions would not be seen as relics of the past but as living, evolving systems that coexist with global faiths. The spiritual diversity of the world would mirror its cultural diversity. This would offer a rich and complex landscape of belief that respects humanity’s many paths.

Change to atheism without colonialism

If native religions had remained dominant in colonized regions, the transformation to atheism might have been less fraught than it is with entrenched, imperial religions that often fuel endless feuds. Indigenous spiritual systems are typically more flexible and adaptive, rooted in local traditions and practical aspects of life. They often lack the rigid dogmas and centralized authority structures that characterize many of the major world religions introduced through colonialism.

Native religions tend to be closely tied to cultural and environmental contexts, making them more integrated into daily life rather than enforcing abstract, universal doctrines. This localized and practical focus means that questioning or evolving away from these beliefs might not feel like a betrayal of an all-encompassing, authoritarian system. Instead, it could be viewed as a natural progression or adaptation to changing societal needs.

In contrast, imperial religions like Christianity or Islam often come with strict doctrines, moral absolutes, and a binary worldview of salvation versus sin. These features create deep emotional and psychological attachments, making the rejection of faith feel like a personal and communal rupture. Additionally, the competitive and often hostile relationships between major religions have historically entrenched identities around faith, making any move toward secularism or atheism appear as an existential threat to the group’s unity or survival.

If indigenous religions had persisted, the transition to atheism might have been framed as a shift in worldview rather than a conflict with dogmatic authority. The absence of centuries-long religious feuds, often imported and exacerbated by colonialism, would have removed a significant barrier to questioning or leaving faith systems. Without the burden of religiously driven identity politics and rivalries, societies might have approached atheism as part of a broader exploration of philosophy, science, and humanism, rather than as an attack on deeply ingrained and divisive beliefs.

Conclusion

Colonialism, intertwined with religion, reshaped societies in profound and often destructive ways. It imposed artificial borders, dismantled traditional governance, exploited natural resources, and forced rigid, foreign values upon diverse cultures. The introduction of imported religions served as both a tool for domination and a force of cultural erasure, replacing indigenous spiritual systems with frameworks designed to control and suppress. While some found ways to resist and adapt, the legacies of this era continue to fracture societies, fuel conflicts, and undermine equality.

The long-term impacts of colonialism demonstrate that it did not bring progress—it disrupted it. Regions that could have thrived independently were left impoverished, divided, and dependent. The erasure of indigenous knowledge, spiritual systems, and cultural identities remains a global loss. As we analyze this history, it is clear that colonialism was not a civilizing force but an act of calculated destruction, the effects of which linger in the social, economic, and spiritual wounds of today.

The resilience of colonized peoples, however, shows that survival and resistance are deeply ingrained in human history. Despite the trauma inflicted, indigenous traditions, values, and identities continue to find ways to flourish, reclaiming spaces in a world still shaped by colonial legacies. Understanding and confronting this history is essential to building a more just, equitable, and culturally diverse future.

Leave a Reply