People think science is about genius. One great mind, one breakthrough, one flash of insight. But in truth, scientific achievement depends on many kinds of intelligence. And those kinds peak at different times.

The myth of a single IQ peak

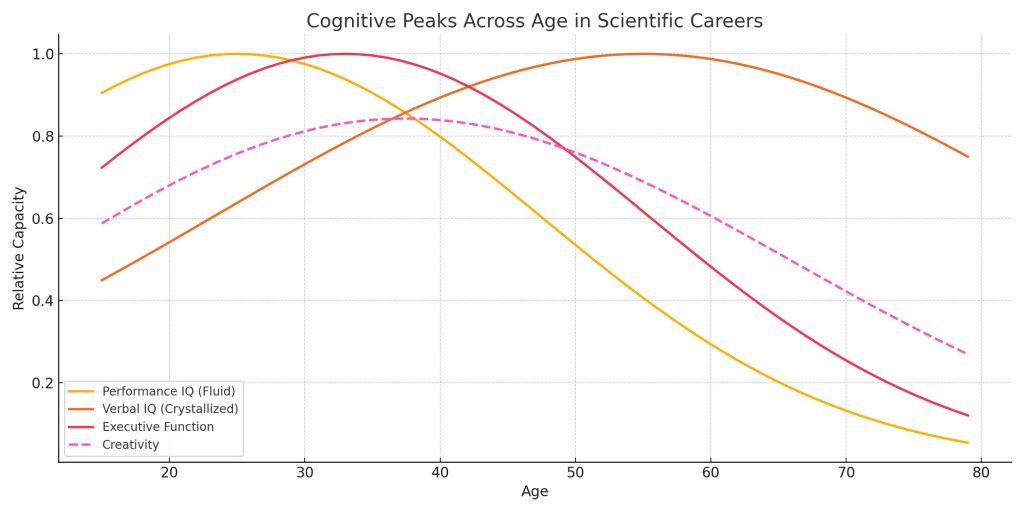

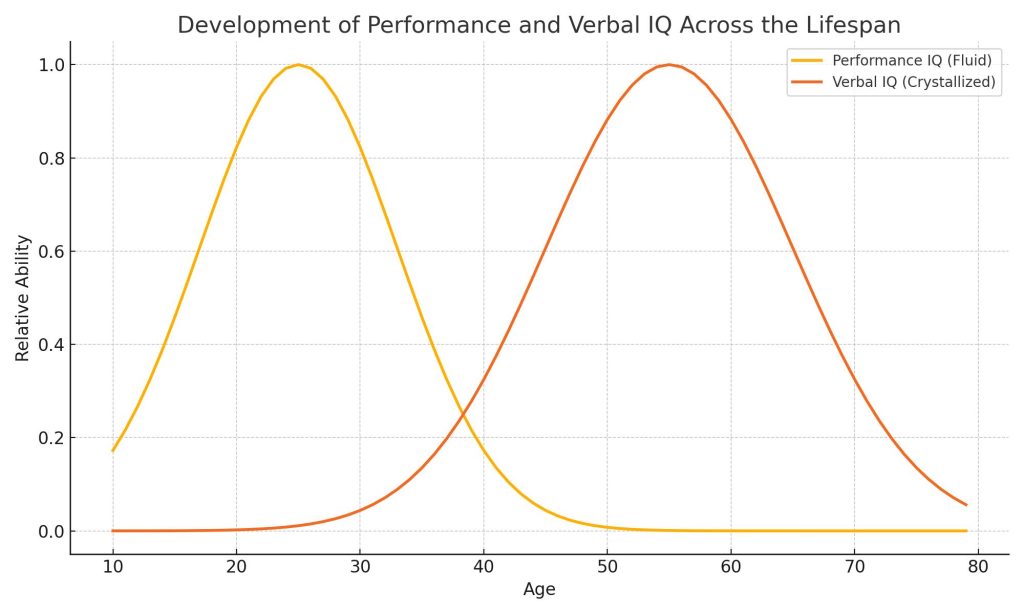

IQ is not one thing. It splits. Performance intelligence (fluid) handles abstract reasoning and novel problems. Verbal intelligence (crystallized) stores knowledge, vocabulary, and conceptual depth. Each matters in science—but they peak at different ages.

Performance intelligence rises early. It hits hard in the early to mid-20s. This favors mathematics, physics, and fields that need speed, novelty, and mental rotation. But it also fades fast.

Verbal intelligence builds slowly. It matures over decades. It can peak in the 50s, even the 60s. This supports disciplines that rely on synthesis, comparison, and real-world complexity. Philosophy, biology, and medicine all benefit.

So the peak of a scientist depends on what they do.

What are performance and verbal intelligence?

Intelligence is not one fixed trait. It unfolds across multiple domains. Two of the most studied are Performance IQ and Verbal IQ.

Performance IQ—originally called Fluid Intelligence—is the ability to reason, solve novel problems, and identify patterns. It thrives without prior knowledge. Think of puzzles, logic games, or fast-changing variables. It operates in real-time. And it’s often what young scientists excel at.

Verbal IQ—once known as Crystallized Intelligence—is accumulated knowledge. It stores vocabulary, factual recall, and conceptual depth, it supports reading, writing, explaining, and comparing ideas. It matures with time and learning. Older scientists tend to shine here.

These two forms of intelligence were rigorously explored by researchers like Raymond Cattell and John Horn in the mid-20th century. Cattell first proposed the fluid-crystallized model in 1963. Horn extended it with studies that showed how these intelligences diverge across age.

Today, cognitive scientists use advanced tools—like Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) subtests, reaction-time tasks, and neuroimaging—to measure how different parts of the brain engage in these types of reasoning.

How did we come to know this?

Studies began with psychometric testing. Researchers noticed that children excelled at certain tests while adults performed better on others. Over decades, longitudinal studies followed thousands of individuals to measure how cognition evolved.

The findings were striking:

- Performance IQ peaks around age 20–30, then declines slowly.

- Verbal IQ rises steadily until the 50s or 60s, and stays robust well into old age.

- Certain executive functions (like planning and emotional regulation) peak in the early 30s.

- Creative productivity often mirrors these curves, depending on domain.

Neuroscience backed this up. Imaging shows working memory, processing speed, and cognitive flexibility are strongest in youth. But semantic memory, judgment, and conceptual integration strengthen with experience.

These discoveries gave shape to a more realistic understanding of scientific potential. They replaced the myth of the young genius with a map of how thinking changes over time—and how different sciences benefit from different peaks.

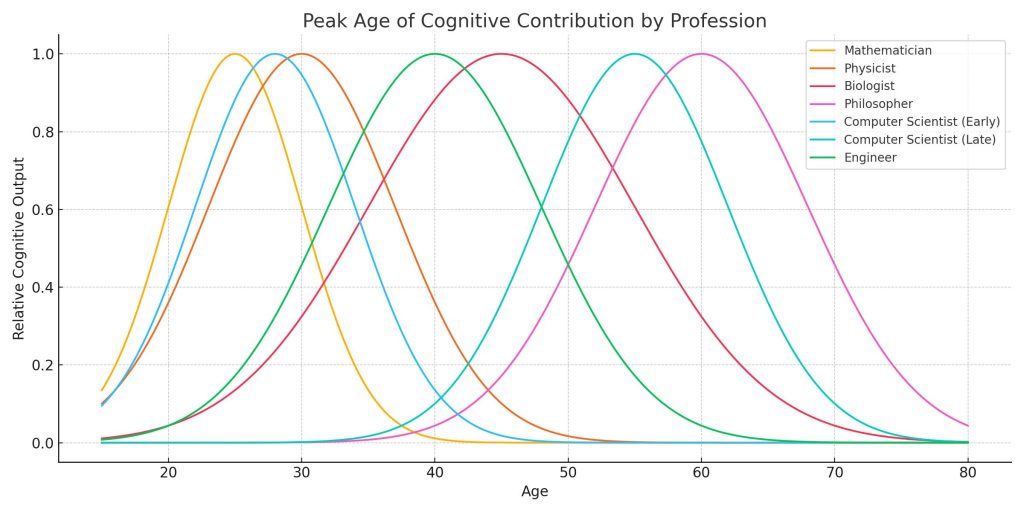

Fields of early firepower

Some fields burn bright early. Mathematicians often publish their best work before 30. Theoretical physicists, too. Newton invented calculus in his 20s. Einstein reshaped the universe before 30. Évariste Galois, a pioneer of group theory, died at 20 after writing foundational mathematics. Paul Dirac developed quantum electrodynamics in his mid-20s.

These disciplines demand fast pattern recognition. Insight must be sharp, fresh, and unconstrained. That favors youth. In these fields, intuition declines fast. Few over 40 make major conceptual breakthroughs.

Fields of late bloom

Other fields reward age. Medical researchers need years of training. Clinical experience matters. Engineers deal with applied complexity. Neuroscientists require long feedback loops. Darwin was 50 when he published “On the Origin of Species.” Gregor Mendel’s work on genetics went unrecognized until later generations.

Here, the brain’s slower faculties win. Verbal intelligence, memory depth, and judgment all matter more. Breakthroughs often happen in the 40s or 50s. Knowledge builds. Systems mature. People refine instead of invent.

Even in fields once dominated by youth, later peaks are rising. AI tools extend capability. Lifelong learning reshapes the curve. The timing is changing.

IQ? Intelligence alone is not enough

IQ matters. But it is not destiny. Many traits shape a scientist’s peak. Executive function—the ability to plan, resist distraction, and manage attention—peaks in the early 30s. Curiosity can rise for life. Emotional resilience builds with age.

Creativity needs more than smarts. It needs risk-taking, failure tolerance, and obsession. Some geniuses burn out early. Others grind for decades before they strike gold. Take Richard Feynman—an early star who sustained innovation across decades. Or Barbara McClintock—who won a Nobel in her 80s.

Beyond this, science draws on talents tied to—but not reducible to—IQ. Pattern recognition, analogical thinking, emotional intelligence, and even linguistic or visual-spatial gifts all play roles. A scientist might struggle with mental rotation but thrive in symbolic abstraction. Another might be weak in logic but brilliant in synthesis.

Moreover, human cognition is not one road—it’s a landscape of strategies. People use entirely different cognitive pathways to reach the same discovery. Some think in pictures. Others in words. Some simulate systems. Others test intuitions. There are infinite mental strategies—combinations of memory, intuition, analysis, and creativity—that lead to scientific success.

Creativity peaks, influence lingers

Many scientists reach their creative peak early. But their impact grows later. Some write their famous paper at 28. But they shape institutions at 48. Others start slow but end as giants.

Mentorship matters. Funding shapes science. Leadership directs entire fields. Influence has its own peak. And it often comes long after the flash of youthful genius fades. Carl Sagan popularized science in his later years. Freeman Dyson contributed meaningfully into his 80s.

Peaks: Every field has its rhythm

Mathematics peaks young. So does theoretical physics. Psychology and economics allow multiple peaks. Biology demands mid-career integration. History of science, philosophy, and ethics peak late. These need breadth, maturity, and long reflection.

Even in computer science, two peaks appear. One early, for code and algorithms. One later, for systems design and ethical control. There is no single curve. Each science has its shape. Noam Chomsky revolutionized linguistics in his 30s but continued making philosophical contributions into his 80s.

External forces shape the curve

Life gets in the way. Tenure clocks force output. Parenthood steals time. Institutional politics cause delays. Burnout hits hard.

Some scientists retire early. Others re-peak after retirement. Some write their masterpiece after losing everything. IQ matters, but context wins. Consider Srinivasa Ramanujan, whose late discovery and early death created an unusual spike. Or Jane Goodall, who built insights over decades.

Artificial intelligence reshapes the timeline

AI extends the curve. Scientists now work longer and better. Algorithms analyze data. Models generate hypotheses. Aging minds no longer lose their edge as fast.

AI shifts the frontier. Young scientists work faster. Old scientists stay useful. The peak is flattening. Tools like AlphaFold changed biology—and let mid-career scientists contribute beyond traditional bounds.

Scientific life is no longer linear

Many scientists peak twice. Once as creators. Once as curators. Others shift fields. A chemist becomes a historian. A physicist moves into ethics. Some burn out. Some explode late.

Science has room for all arcs. Early stars. Mid-life bloomers. Late giants. The system rewards timing—but it does not demand a clock.

Final insight

There is no one peak. Science rewards different minds at different times. What matters is not how early you rise. It is how long you evolve.

A theory can come from a 22-year-old with a whiteboard. Or from a 60-year-old with a library. The mind that dares, survives.

That is science.

Leave a Reply