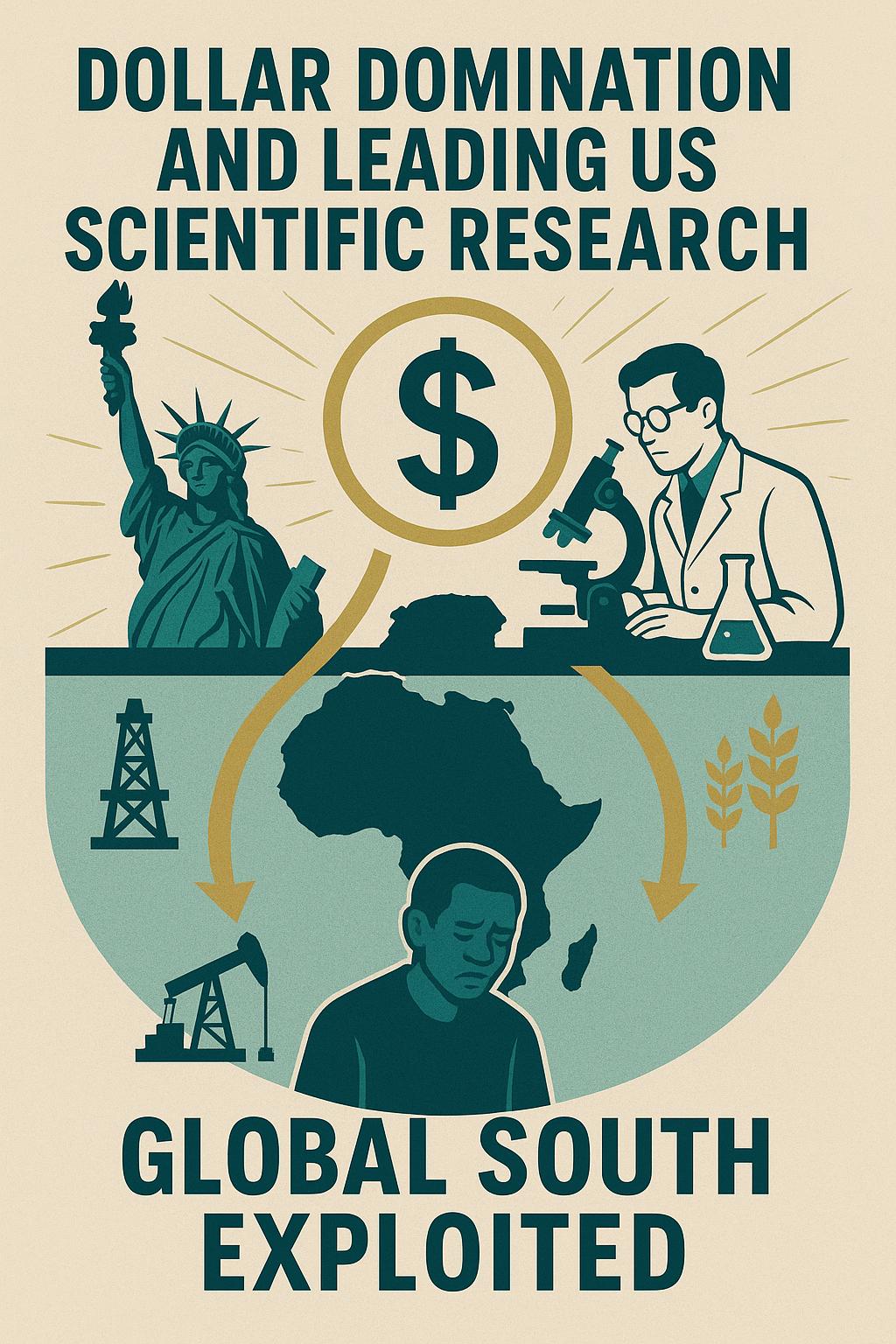

The United States stands as the world leader in science. It also controls the world’s money. These two powers are not separate achievements. They are deeply connected. The financial supremacy of the dollar provides the material basis for American research. Without this advantage, U.S. science would look very different. The Global South, on the other hand, pays the cost. It lacks reserves, it cannot afford the same investments, and it remains trapped in dependency.

Dollar domination as a foundation of power

The dollar did not become dominant by accident. After the Second World War, the Bretton Woods system gave the United States the central role in rebuilding the financial order. Currencies were pegged to the dollar, and the dollar was pegged to gold. This arrangement turned the U.S. into the anchor of the global economy.

When President Nixon ended the gold standard in 1971, many expected dollar supremacy to fade. Yet it did not. Oil continued to be traded in dollars. Global markets relied on U.S. banks and Wall Street. Trust in American institutions remained stronger than in any rival system. By the 1980s the dollar was no longer simply a currency. It became a political weapon, a measure of stability, and a symbol of global order.

Today, almost every international transaction involves the dollar. Around 60 percent of global reserves are held in it. Over 80 percent of trade finance is settled through it. Countries from Africa to Asia must secure dollars to pay debts, buy fuel, and stabilize their exchange rates. This dependence gives Washington enormous leverage. A single interest rate hike by the Federal Reserve can push dozens of weaker economies into crisis.

Exploitation of the Global South

The Global South pays the highest price for this system. Most of these countries do not have large reserves. They must use what little they hold to defend their currencies and to repay loans denominated in dollars. This means they cannot use the same money to build laboratories, fund universities, or train scientists.

Instead of investing in research, governments spend billions on interest payments. The World Bank and the IMF often demand austerity as a condition for loans. That means cutting health budgets, shrinking education programs, and freezing science funding. Every crisis brings another wave of cuts. Science becomes a luxury that poor countries cannot afford.

Natural resources make the exploitation worse. Africa provides minerals essential for modern technology. Latin America exports agricultural products and oil. Yet profits flow back to multinational corporations and Western banks. Local universities see almost nothing of this wealth. The result is a paradox: regions rich in resources remain poor in science.

Another dimension is brain drain. Bright students from Nigeria, India, or Brazil seek better futures abroad. They move to the United States or Europe, where salaries are higher and conditions are stable. They often never return. The countries that financed their early education lose their best minds just when they could contribute to local development. The Global South not only loses reserves but also loses the human capital needed for independent science.

Even intellectual independence suffers. Scientific journals are almost all based in the West. Access to them requires high subscription fees that many Southern institutions cannot afford. Grants come from U.S. or European foundations, which set research priorities according to their own interests. Local science becomes dependent on foreign approval. That is not autonomy. It is exploitation hidden under the language of cooperation.

US scientific leadership and its financial base

The United States enjoys the opposite conditions. Because dollars flow inward, the government can fund massive science programs. The National Science Foundation spends over $10 billion per year. The National Institutes of Health budget is nearly $50 billion. NASA operates with resources larger than the entire science budgets of entire continents.

American universities stand on this foundation. Harvard, MIT, Stanford, and Berkeley command endowments worth billions. They attract the best researchers worldwide by offering salaries and funding impossible to match elsewhere. Laboratories purchase the most advanced equipment, while private companies like Google, Microsoft, and Pfizer add billions more in private research investment.

This environment generates constant discovery. From biotechnology to space exploration, from artificial intelligence to physics, U.S. science dominates because it has money. And it has money because the dollar rules the world.

The role of Anglo-Saxon culture

Yet culture also matters. Anglo-Saxon traditions shaped the institutions that now define modern science. Empiricism in England, pragmatism in America, and freedom of inquiry formed the backbone of the scientific method as practiced today.

Peer review, open debate, and merit-based competition emerged strongly in Anglo-American contexts. They did not eliminate inequality or bias, but they created a framework where science could thrive beyond national or religious authority. English became the global language of science, not only by accident but also by cultural dominance.

This cultural environment is often treated as “necessary.” It creates transparency, international cooperation, and common standards. But it also excludes other traditions. Indigenous knowledge systems, non-Western epistemologies, and alternative approaches are often dismissed as unscientific. Anglo-Saxon culture does not just enable science. It also defines what counts as science.

Interaction of money and culture

The American system combines both pillars. Dollar supremacy provides the financial infrastructure. Anglo-Saxon culture provides the intellectual one. Together they sustain U.S. scientific leadership. Neither alone would be enough.

The Global South lacks both. Without reserves, it cannot fund science at scale. Without cultural dominance, it cannot shape the global scientific agenda. Even countries with talent and ambition—like India or Brazil—face barriers that are systemic, not individual. They are forced to play by rules they did not design.

China as a partial exception

China presents a different picture. It holds the largest foreign reserves in the world, over three trillion dollars. It uses these reserves not only to stabilize its currency but also to invest massively in research and development. Its science budget is second only to that of the United States.

Chinese universities and institutes produce a vast number of publications. The country has built laboratories, launched space missions, and advanced in fields from quantum computing to biotechnology. It also funds projects that many Global South nations can only dream of.

Yet problems remain. China’s education system is rigid, exam-driven, and hostile to creativity. It trains millions of engineers and scientists, but it does not allow the most brilliant individuals to rise to the top. Talent is filtered through memorization, obedience, and conformity. The system rewards those who master rules, not those who break them with innovation.

Top minds cannot climb the ladder

As a result, China produces enormous quantity but often struggles with originality. The very top minds cannot climb the ladder because the ladder itself is designed for discipline, not genius. Many of the most gifted Chinese researchers either leave for the United States or remain underutilized at home.

Even when breakthroughs occur, global recognition depends on publishing in English-language journals. Cultural barriers make Chinese discoveries less visible. Anglo-Saxon culture still defines the standards, and the gatekeeping remains firmly in Western hands.

Moreover, despite its vast reserves, China’s financial system remains tied to the dollar. Exports are priced in dollars, and reserves are parked in U.S. Treasury bonds. American monetary policy still affects Chinese stability. That makes China a partial exception, not a full alternative.

It shows that reserves can buy laboratories, equipment, and infrastructure. But it also shows that education, culture, and dollar dependence still hold back true leadership. China rises, yet the rules of the game remain written elsewhere.

Concrete examples of disparity

Consider Nigeria. Its universities struggle with electricity shortages, outdated equipment, and low pay. The government spends more on debt service than on education and research combined. Young scientists often leave, creating a vicious circle.

Brazil once built a strong biomedical sector. Yet repeated currency crises and austerity measures hollowed it out. Research budgets fell while interest payments to foreign creditors soared. The country produces excellent scientists, but its institutions remain underfunded.

India is often celebrated for its IT sector, but its science funding per capita remains a fraction of U.S. levels. Its best graduates fill laboratories in Boston or Silicon Valley, while domestic research struggles with bureaucracy and underinvestment.

These examples show a pattern. Without reserves, countries cannot protect science from economic shocks. Without financial freedom, they cannot invest long term.

Conclusion

The United States sits on top of global science because it also sits on top of global finance. The dollar provides endless reserves. Reserves create research. Research reinforces power. The cycle continues.

The Global South pays for this dominance with debt, austerity, and brain drain. It loses resources, it loses people, and it loses its chance to build strong scientific communities. Unless the global order changes, this gap will remain permanent.

China shows that large reserves and state commitment can produce rapid scientific growth. Yet it also shows that even massive investment does not fully escape dollar dominance or Anglo-Saxon cultural hegemony.

Dollar domination is not just about trade or markets. It is about knowledge, discovery, and who gets to define the future. The U.S. holds the keys because others have been locked out.

Leave a Reply