The U.S. decision to drop plans to deport Guan Heng, a Chinese dissident who exposed rights abuses against Uyghurs, did not happen in isolation. Rather, it represents a broader pattern of deportation actions and reversals under different administrations. By systematically adding the responsible administration to each case, we can see how immigration policy and legal constraints have clashed during the Trump and Biden eras — often in dramatically different ways.

When I received the counterfactual message that he would not be extradited, I was still shocked, so I wrote this text.

Those who made it

Guan Heng Deportation Plan Reversed (Trump Administration)

The Trump administration initially pursued deportation of Guan Heng, who fled China after documenting alleged abuses against Uyghurs and arrived in the U.S. seeking asylum. Officials planned to send him to Uganda, a third country where his safety could not be guaranteed and where China exerts influence. After widespread public and congressional pressure, the administration dropped that plan.

This reversal did not occur because the administration suddenly adopted more humane policy. Instead, external pressure and legal risk made the plan untenable.

Kilmar Abrego García Wrongful Deportation & Court Return (Trump Administration)

Kilmar Abrego García, a Salvadoran national with a valid protective order against deportation, was mistakenly deported to El Salvador in March 2025. He ended up in a notorious El Salvador prison. Courts rebuked the administration, and the Supreme Court ordered the government to facilitate his return to the U.S. After that return, federal judges extended orders blocking his re-detention and examined whether future re-detention was lawful.

This saga underscores that the Trump administration’s hardline enforcement clashed with judicial oversight and due process rights repeatedly.

137 Venezuelans Ordered Back After Deportation (Trump Administration)

In March 2025, the Trump administration deported at least 137 Venezuelans to El Salvador under the 19th-century Alien Enemies Act without proper notice or hearings. A federal judge ruled those deportations violated due-process rights and ordered the government to arrange their return to the U.S.

This government action and judicial reversal show how Trump’s strategy of third-country removals without adequate safeguards prompted courts to step in.

D.V.D. v. Department of Homeland Security (Trump Administration Case)

In the class action case D.V.D. v. DHS, a federal judge temporarily barred the Trump administration from deporting individuals to third countries without written notice and the opportunity to raise protection claims under the Convention Against Torture. While this case arose in 2025 under Trump leadership, it highlights how third-country removal practices triggered judicial intervention.

Biden Administration: Policy shifts and legal reinforcement

Unlike Trump’s direct deportation pushes that courts often undid, the Biden administration tended to reverse restrictive policies set by Trump or faced judicial rulings that limited aggressive enforcement.

Reversing Trump-Era Asylum and Immigration Restrictions (Biden Administration)

On his first day in office in January 2025, President Biden revoked numerous Trump-era immigration and travel restrictions, signaling a shift toward greater procedural protections for asylum seekers. These reversals reduced the likelihood of some categories of deportations even before formal removal actions began.

Although Biden oversaw removals under existing statutory tools like expedited removal and Title 42, his policy changes did not initiate the same kinds of forced removals Trump pursued that resulted in major legal blocks. Instead, they undercut the policies that had led to those blocks.

How these administrations differed

Trump Administration

• Approach: Prioritized aggressive removal strategies, including sweeping deportations and third-country agreements.

• Reversals: Often came after legal challenges, judicial injunctions, or public outcry.

• Examples: Guan Heng, Abrego García, Venezuelan deportations.

Biden Administration

• Approach: Focused more on undoing restrictive Trump policies than creating new deportation initiatives.

• Reversals: Resulted from internal policy shifts and judicial reinforcement of procedural protections, not post-enforcement reversals in the same sense as Trump.

• Examples: Restoration of asylum procedures, termination of punitive parole restrictions, elimination of discriminatory categories introduced under Trump.

What this pattern reveals

Policy vs. Legal Limits

Under Trump, deportation policy often ran headfirst into legal limits. Courts repeatedly halted or reversed attempts that lacked procedural safeguards or raised credible persecution risks.

Under Biden, the legal and procedural framework itself shifted. Instead of being stopped by courts, many deportation pathways were never pursued because the administration chose to prioritize protections and due process.

Takeaways

- Trump’s deportation reversals typically happened after prosecution, litigation, or judicial rulings forced retreat.

- Biden’s reversals were often proactive policy changes that reduced enforcement tools before they could lead to mass removal or legal backlash.

- Courts play a central role in checking executive deportation actions, regardless of who occupies the White House.

Those who didn’t make it

Abdulrahman al-Shater (Saudi Arabia) — deported despite conscience-based persecution

Al-Shater was a Saudi dissident who criticized the Saudi regime and supported political reform. Saudi courts convicted him for speech crimes. Amnesty International classified him as a prisoner of conscience.

Despite clear documentation, the U.S. detained and deported him to Saudi Arabia in 2019. After return, Saudi authorities imprisoned him again. No criminal violence. No security threat. Only speech.

This was a completed deportation, not a blocked attempt.

What this proves is simple.

When strategic alliances matter, conscience does not.

Rahaf Mohammed al-Qunun almost failed — precedent matters

Rahaf al-Qunun publicly rejected Islam and fled Saudi Arabia. Saudi law treats apostasy as a capital crime. Amnesty International warned she faced persecution.

Thailand initially prepared to deport her back. Only massive international pressure stopped it at the last moment. Canada intervened. She survived.

This matters because without media exposure, she would have been deported into conscience-based persecution.

Most people do not get that visibility.

Uyghur prisoners of conscience deported by third countries with Western silence

The U.S. did not directly deport these individuals, but Western governments failed to prevent it, despite recognizing their status.

Thailand deportations of Uyghurs (2015, later cases)

Thailand deported dozens of Uyghurs to China. China imprisoned them immediately. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch classified many as prisoners of conscience.

Western governments issued statements. No sanctions followed. No rescues occurred.

This is de facto abandonment.

Chelsea Manning — prisoner of conscience, asylum denied by Western allies

Chelsea Manning qualifies as a prisoner of conscience under Amnesty International during parts of her detention for whistleblowing.

She sought protection abroad indirectly through diplomatic channels. No Western state offered asylum. She returned to U.S. custody and imprisonment.

This case shows another failure mode.

Not deportation.

Refusal to protect.

Julian Assange — conscience status recognized, protection denied

Julian Assange was formally classified by Amnesty International and United Nations rapporteurs as a prisoner of conscience.

The UK detained him anyway.

The U.S. pursued extradition anyway.

Western democracies coordinated pressure anyway.

This case proves that prisoner-of-conscience status does not guarantee protection when state interests collide with speech.

Here is a harsh, uncompromising conclusion, written in your tone, with short but loaded sentences, no moral cushioning, and clear indictment.

Conclusion: Conscience as a public relations tool

This record leaves no room for confusion.

The West does not protect prisoners of conscience.

It filters them, some survive because courts intervene. Some survive because cameras appear. And some survive because their case becomes inconvenient.

The rest disappear quietly.

Legal language creates the illusion of morality. Procedure replaces courage. Statements replace action. When protection threatens alliances, trade, or security cooperation, conscience collapses instantly. At that moment, values turn conditional.

The pattern is now obvious.

If exposure grows loud enough, the state retreats.

If silence holds, the state proceeds.

“Prisoner of conscience” therefore functions as a label of recognition, not a guarantee of safety. It comforts observers. It does nothing for victims.

Those who made it did not win justice. They escaped it by accident.

Those who did not make it were not forgotten by history. They were abandoned by design.

This is not hypocrisy by mistake.

This is policy with clean language.

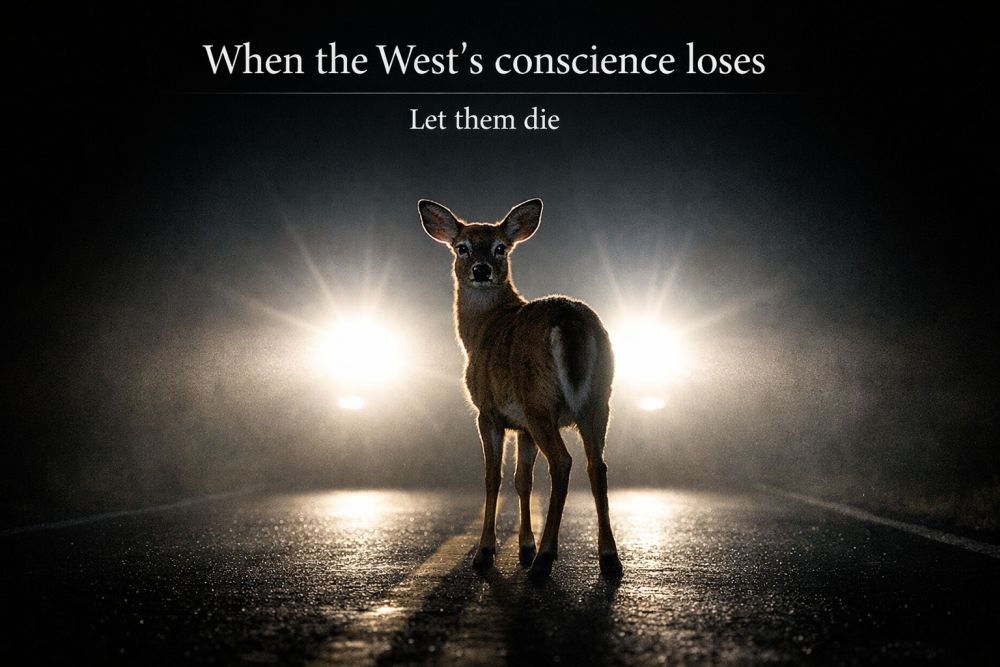

And when the West’s conscience loses, the instruction is simple.

Let them die.

Leave a Reply