Organized crime is not born as a giant. It begins with independent gangs, small groups of criminals who control a street corner, a bar, or a neighborhood. Over time, these gangs expand, form alliances, and build networks. Eventually, they grow into a parallel power structure that rivals the state.

It kills individuals, but it also destroys entire communities and even whole states. It undermines trust in institutions, corrupts leaders, and makes violence routine. Traditional methods—police raids, mass imprisonment, tougher laws—have failed. The reason is simple. Organized crime thrives on prohibition and illegality. Where the state bans, the mafia profits. If we legalize, regulate, and tax, we take away its foundation.

The roots of organized crime

Black markets create vast profits where demand is high but supply is forbidden. Illegality raises prices, making violence, bribery, and secrecy worthwhile. Prohibition is the mother of the mafia. When the United States banned alcohol, it did not kill drinking. It created empires for Al Capone and others.

Even after a century, the legacy of prohibition is still alive. Families that built fortunes during those years remain strong and rich. They reinvested their profits, diversified their businesses, and spread into drugs, gambling, and construction. What was meant to destroy crime instead made it permanent. Prohibition proved that once a mafia family grows fat on a black market, it rarely disappears. It adapts and survives for generations.

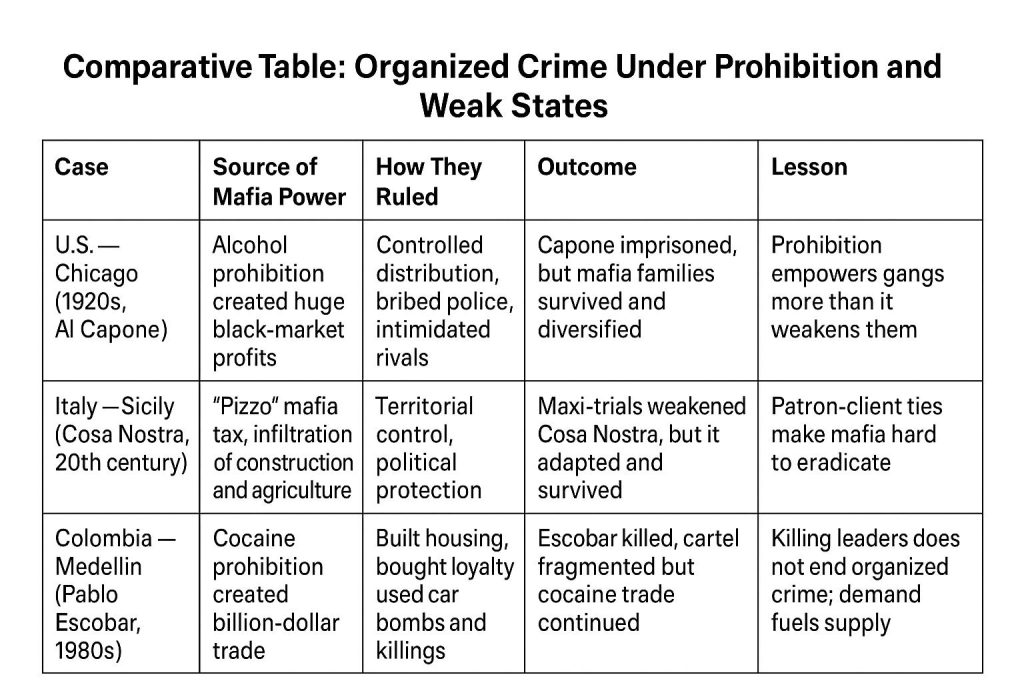

Chicago in the 1920s showed how prohibition could transform a city into a battlefield. Al Capone’s empire made millions weekly from bootleg liquor. Politicians and police officers were on his payroll. Ordinary people respected him because he offered jobs and protection when the state failed. In reality, it was terror disguised as generosity. The U.S. government learned too late that prohibition had handed power to criminals.

Unlike terrorism, organized crime does not want headlines. It wants to be invisible. Its power grows in silence. It rules territories, controls lives, and makes fortunes without the public noticing. Terrorists show their power in explosions. Mafias show it in contracts, bribes, and quiet killings.

Inept citizens

In the United States, during the peak of organized crime, the country resembled Russia of today. Criminal families did what they wanted, unchecked by weak institutions. Cities like Chicago and New York looked more like fiefdoms than republics. Politicians and police were bought, journalists silenced, communities ruled by fear. Citizens themselves were too inept or too powerless to resist. Only when super-rich families, major corporations, and powerful banks asserted dominance did organized crime lose ground.

The same pattern holds in Russia today. Citizens are sidelined, institutions are captured, and organized crime blends with oligarchs, secret services, and local authorities. Just as American elites once marginalized the mafia by replacing its networks with their own financial power, Russian oligarchs and state security services today dominate the underworld instead of destroying it. Both cases show a painful truth: when ordinary people are too weak, elites decide whether the mafia thrives or fades.

Two forms of directing mafia

Mafias are not random street groups. They follow clear structures. There are two main forms.

The first is the patron–client system. Here, loyalty is based on mutual obligations. Local bosses provide protection, money, or favors. In exchange, their clients deliver silence, votes, or smaller services. This system is flexible, deeply hidden, and often tied to the community. Villagers in Latin America depend on cartels for schools or food. Families in Southern Italy vote as their local padrone tells them. It is not only about crime. It is about survival. Because of its informal nature, proving it is difficult. Even when evidence surfaces, outsiders often doubt its existence, since it rests on invisible ties rather than signed orders.

The second is the direct hierarchical system. This looks more like a corporation or an army. Orders flow from the top boss to captains, lieutenants, and soldiers. Discipline is enforced through fear, torture, and killings. It is less flexible but highly effective in controlling massive trades like drugs or arms. Cosa Nostra in its peak or modern Mexican cartels show this ruthless efficiency. And unlike the patron–client system, once documents, ledgers, or communications are retrieved, everyone is convinced. The chain of command is visible on paper. It leaves little room for denial.

Sometimes both forms overlap. Patron–client ties help mafias gain legitimacy. Direct hierarchy ensures total obedience. Together, they form the backbone of organized crime.

Territorial control and criminal taxation

Organized crime does not only run businesses. It also rules territories. In many countries, whole neighborhoods, villages, or even provinces fall under mafia authority. Anyone who commits a crime inside these areas must pay them. A thief who steals cars must hand over a share. A drug dealer who sells independently must pay a tax. Even small businesses are forced to contribute.

This is not simple extortion. It is a parallel system of governance. The mafia acts as judge, tax collector, and executioner. It decides who may operate and who must disappear. In such areas, the state is no longer sovereign. The mafia is.

The most famous case came from Sicily. For decades, Cosa Nostra demanded a “pizzo” — a mafia tax paid by shopkeepers, bar owners, and construction companies. Refusal meant arson or murder. It was so normalized that many Sicilians saw it as unavoidable, like paying electricity. Only with the maxi-trials of the 1980s, when prosecutors like Falcone and Borsellino gathered overwhelming evidence, did the world finally understand the scale of mafia control. But the victory was partial. Both men were later assassinated, proving how deep mafia power still ran.

Medellín in the 1980s showed a similar pattern. Pablo Escobar’s cartel controlled not only cocaine routes but entire districts of the city. He built housing for the poor, sponsored football teams, and presented himself as a benefactor. At the same time, he ordered car bombs, assassinated judges, and murdered presidential candidates. In Medellín, the state was secondary. Escobar was the real authority.

Services and products controlled by organized crime

The mafia exists because it provides services and products the state bans or cannot deliver. These include drugs like cocaine, heroin, meth, and cannabis. They also include prostitution, gambling, arms smuggling, and human trafficking.

But it goes further. Mafias control extortion and protection rackets. They sell counterfeit goods, smuggle migrants, and even trade organs, they dominate illegal logging, mining, and toxic waste disposal. They run cybercrime rings, stolen car networks, and underground loans. Some even sell contract killings. In short, wherever there is demand, organized crime steps in.

What legalization could take away from organized crime

If the state legalizes and regulates, mafias lose their power. Legal drug markets, controlled distribution, and taxation destroy cartels’ biggest revenue stream. Regulated sex work protects workers and makes pimps unnecessary. Gambling moves into safe casinos and licensed online platforms.

Microloans and transparent banking remove the need for mafia lenders. Trust in police and courts eliminates protection rackets. Legal alcohol and cigarettes kill smuggling profits. Consumer protection reduces demand for counterfeit goods.

Legal work visas take the income from migrant smugglers. Regulated arms trade weakens traffickers. Transparent organ donation programs undermine organ harvesting. State waste management removes profits from toxic dumping. Legal concessions stop illegal logging and mining. Transparent car registries end stolen car networks. And with better regulation of digital currencies and online identity, cybercrime markets collapse.

Finally, contract killings lose their point when disputes can be solved legally. Every “service” of the mafia can be either legalized, regulated, or replaced by the state.

Legalization as a tool of dismantling

By legalizing, the mafia loses its markets; by regulating, the state gains control. By taxing, communities gain resources. The logic is simple. Violence, torture, and murder exist because disputes in black markets cannot be settled in court. Remove the black market, and you remove the blood.

Effects on violence and torture

Mafia torture is not random sadism. It enforces contracts in illegal economies. Killings are signals of power and control. But when industries become legal, violence becomes unnecessary. Courts and police replace torture chambers. Corruption of judges and officers declines when billion-dollar bribes vanish.

Impact on states and communities

Organized crime weakens states from the inside. It corrupts police, judges, and even ministers. It builds loyalty based on fear, not law. Communities collapse under constant extortion. People live in silence, not trust. Whole countries fall into narco-states or mafia-states, from Mexico and Colombia to Afghanistan and parts of Africa and the Balkans.

Legalization and regulation reverse this collapse. The state regains legitimacy. People trust institutions instead of gangs. Communities are freed from extortion and fear.

Here is an additional section you can insert into your article, focusing on a real failed state that collapsed largely because of organized crime — Somalia.

Somalia: a state consumed by organized crime

Somalia offers one of the clearest examples of how organized crime can destroy an entire country. When the central government collapsed in 1991, armed clans, smugglers, and warlords filled the vacuum. Without functioning institutions, organized crime became the only authority.

Piracy off the Somali coast became infamous worldwide. Armed groups hijacked ships, extorted ransom payments, and disrupted global trade. But piracy was only one side of the story. Smuggling networks thrived on weapons, drugs, and people. Black markets became the backbone of the economy. Communities paid “taxes” to warlords instead of the state.

What emerged was not chaos in the sense of randomness. It was a criminal order. Territories were controlled, rules enforced, and money collected. Yet all of this happened outside the framework of the state. Ordinary people suffered, while warlords and traffickers grew rich.

Somalia shows the endpoint of unchecked organized crime. It begins with gangs, grows into cartels, and ends with the destruction of the state itself. Once institutions collapse, rebuilding them becomes almost impossible.

No organized crime in communism

In communist states, organized crime could not flourish because the conditions that normally fuel it were absent. There were hardly any luxury goods available — no villas, fancy cars, or expensive electronics to trade or smuggle — and without demand, black markets remained weak. Extorting state institutions was impossible because the economy was fully nationalized and guarded from within. Harsh repression meant that any gang showing ambition was crushed immediately. On top of that, tightly guarded borders prevented contraband from flowing in. What little crime existed stayed local and marginal, never able to grow into a parallel power.

Counterarguments and responses

Critics fear moral decline. But regulation protects society, it does not encourage vice. Critics fear mass addiction. Yet public health policies work better than police repression. Critics fear chaos. But real chaos comes from underground markets, not from legal transparency.

Beyond legalization: weakening organized crime further

Legalization is the first step, not the last. States must also fight money laundering, sever mafia–political ties, and cooperate internationally against trafficking. Civil society must replace mafia services with real institutions. Communities must see that the state, not the mafia, provides security and opportunity.

Conclusion

Organized crime flourishes only where states create black markets. When the state legalizes, regulates, and taxes, the mafia suffocates. Its patron–client networks collapse, its direct hierarchies lose their purpose, and its services become redundant. A state that destroys organized crime does not only save individuals. It protects its communities and prevents nations from collapsing.

Leave a Reply