Throughout history, people have struggled to possess something of their own. Not out of greed, but because without ownership, there was no dignity, no safety, no independence. To own even a patch of land, a cow, or a tool was to escape the total control of kings, lords, or masters. However, what began as a battle for personal freedom has now become a mechanism of control. We live in a time where it is possible to own things—on paper. But in practice, ownership has been weaponized. A few trillionaire families, multinational corporations, and giant Big Banks now hold the vast majority of all valuable assets. Everyone else is left with fragments. The world did not abolish feudalism. It simply replaced the sword with the spreadsheet. The fight to possess anything is still with us—but now we face its ugly downsides.

From cooperation to control: The origins of ownership

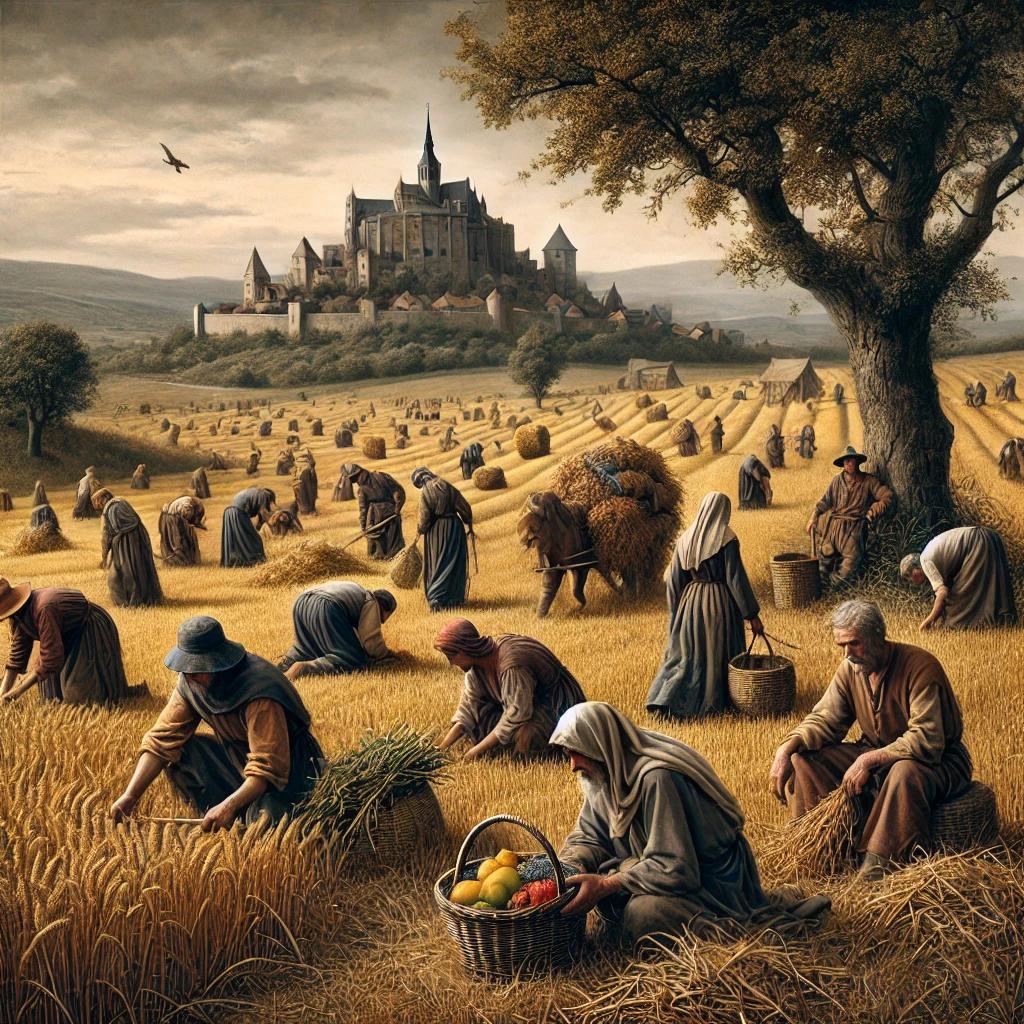

Early human communities did not draw borders around land. They did not issue titles or legal deeds. Instead, they shared food, space, and knowledge. However, once agriculture emerged, everything shifted. People began to settle. They needed to store grain, protect water, and control harvests. That control quickly created hierarchies. Land became power. The more land one had, the more people one could dominate.

It did not take long for elites to claim territory and enslave labor. From Mesopotamia to Egypt to the Indus Valley, landownership defined the ruling class. Beneath them, farmers had no rights. They could not pass their land to their children, nor escape obligations. Religious systems often supported this inequality. Temples and monarchs declared their control sacred, unchallengeable, and eternal.

Over time, those without property lost even the memory of what freedom could mean.

The fight to possess: Feudalism: The long winter of the commoner

The collapse of empires in Europe gave rise to feudal lords. These men carved up land and demanded loyalty from those who lived on it. In return, peasants received just enough to survive. TThey could not leave, choose their work, or negotiate.

Any attempt to resist—whether during the English Peasants’ Revolt, the Bohemian defiance, or the great uprisings in Germany—was met with brutal force. Every castle stood as a monument to this inequality. Meanwhile, the church, often the largest landowner of all, taught that this order was divinely ordained.

By enclosing forests, pastures, and fields, lords removed even the possibility of self-sufficiency. Villagers once grazed animals on shared lands. After enclosure, they paid rent or starved. The concept of personal ownership vanished for centuries, replaced by submission and dependency.

Right to own: Women, slaves, and the locked gates of property

As if class-based exclusion were not enough, entire categories of people were denied ownership because of gender or race. For much of history, women were seen as property before they could ever possess it. In Greece, Rome, and most of medieval Europe, women could not own land, sign contracts, or inherit wealth. Even widows, when allowed to control land, often lost it upon remarriage.

Well into the 20th century, this persisted. In many countries, a woman needed her husband’s permission to open a bank account. She could not take out a loan, own a business, or even have legal control over her children’s inheritance. Financial institutions designed systems that deliberately excluded women.

Meanwhile, the situation for enslaved people was even more extreme. They were legally classified as property. In the Americas, slaves built plantations, towns, and railroads. Yet they were denied all rights. They could not own land, receive wages, or keep their own families intact. Their labor enriched others—those who owned them—and left behind a legacy of systemic dispossession.

The rise of capitalism and the new promise

Feudalism eventually collapsed under the weight of its own inefficiencies. Trade expanded. Cities rose. The merchant class gained influence. For the first time in centuries, ordinary people glimpsed a path toward ownership. Capitalism brought private contracts, portable wealth, and markets. In theory, it opened doors.

Yet most people remained workers, not owners. In early industrial societies, factory owners held immense power. Workers labored for long hours in dangerous conditions. Children crawled under machines. Wages barely sustained families. Few owned their homes. Even fewer had savings or investment. Their value came only from their labor, which enriched others.

Labor unions eventually forced concessions. Shorter workdays, collective bargaining, and safer workplaces became law. Yet even then, ownership remained elusive. Most people worked for others their entire lives, with no control over the companies they built.

The brief expansion of ownership rights

After two world wars and the Great Depression, nations faced immense pressure to reform. The result was the rise of social democracies. In Europe, the United States, Japan, and other parts of the world, governments expanded access to housing, education, and healthcare. Middle-class life became possible. Homeownership rates rose. Pension systems offered stability. Public infrastructure gave people security.

Women gained property rights. Racial discrimination laws began to break down. Workers received benefits that made saving and investment feasible. For a brief few decades, ownership no longer meant exclusion. It represented progress.

But the balance was delicate. Behind the scenes, a new class prepared to reclaim control.

The fight to possess from the different persepctive: The super-rich seize the earth

Since the 1980s, global elites have restructured ownership in ways never seen before. Privatization of public goods, deregulation of markets, the weakening of labor laws, and financial globalization all served one purpose: to return power to the ultra-wealthy.

Massive banks—too large to fail, too complex to regulate—expanded across continents. Investment firms like BlackRock and Vanguard took controlling stakes in nearly every major corporation. Their trillions in assets allow them to dictate executive decisions, suppress wages, resist regulation, and shape economies from above. These institutions own significant portions of the energy, transportation, food, and defense sectors. Yet their names remain unknown to most people.

Super-rich families—many of whom gained their wealth centuries ago—have only grown more powerful. The Rothschilds, Astors, Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, and other dynasties hold wealth passed down over generations. Their wealth is not just money. It includes land, patents, media companies, entire industries. They lobby governments, influence elections, and write legislation in their favor.

This concentration has created a world in which just 1 percent owns more than the bottom 99 percent combined. Worse still, the 99 percent now indirectly “own” the wealthy—not in the sense of control, but through dependency. The working classes rent homes from the rich. They pay interest to their banks, buy groceries from their companies. They generate data that fuels their algorithms. Every transaction, every click, every payment adds another layer of wealth to those already at the top.

A planet for rent

Although people today can technically own property, most of that ownership is structured through debt. Mortgages lock families into financial servitude. Auto loans, credit cards, student loans—all function as levers that keep people from ever accumulating real wealth. Renting has become the norm for housing. Subscription models dominate services. Even software and entertainment are no longer bought, only leased.

Landlords, property developers, and investment groups have turned basic shelter into a source of permanent revenue. In many cities, young people cannot buy homes without family assistance. Even when they can, they buy at inflated prices, handing decades of future earnings to banks and investors.

Moreover, digital platforms have transformed ownership even further. When someone uploads a photo, writes a post, or makes a purchase, their behavior is recorded, sold, and repackaged as data. That data becomes an asset—owned by someone else. People provide the value. Corporations collect the rewards.

From possession to subjugation

Ownership was supposed to liberate. It was supposed to allow people to stand independently, to make choices, to escape dependency. Today, it functions in reverse. Those with assets collect rents. Those without must pay, borrow, or comply.

A person may own a smartphone, but they cannot control the software inside. They may own a car, yet still pay for insurance, fuel, and tolls controlled by others. They may buy a house, only to discover that taxes, neighborhood decisions, and infrastructure are dictated by corporate interests or absentee landlords.

Freedom becomes theoretical. In reality, most people live under the rule of others—not kings, but capital. The mechanisms are quieter. Yet the results are just as unequal.

Reimagining ownership for everyone

This system did not emerge by accident. Nor is it inevitable. It was built, piece by piece, through law, finance, policy, and ideology. And it can be changed.

True ownership must be redefined. It must mean not just legal possession, but control, stability, and autonomy. That requires deep reforms. Universal housing rights. Public banks. Shared ownership models. Worker cooperatives. Open-source digital platforms. Community land trusts. Inheritance taxation. Wealth transparency. Democratic control over essential resources.

Ownership must no longer serve as a dividing line between rulers and ruled. It must be a foundation for shared power.

The fight has only shifted

In the past, people fought to own because without property, they had no hope of dignity. Today, the conditions are different, but the stakes are the same. Although people now possess goods, the system that structures ownership has become predatory. It extracts, isolates and exploits.

The 99 percent do not just suffer inequality. They carry the weight of the global elite’s wealth on their backs, fund it. Also, they sustain it. They enable it—every day.

Yet that system, like the ones before it, can be resisted. People have pushed back before. They have organized, reclaimed, rebuilt.

Now is the time to do so again—not to discard ownership, but to restore its original promise: freedom, dignity, and equality for all.

Leave a Reply