Two Caucasian mothers with strollers, caring for babies, are talking to each other. Mothers who should be raising their children keep switching discussion topics as they stroll. And one of them says: “They should really gas the Gypsies!” The other one nods.

Do you think this is a form of art or some fantasy? No, it is the naked Czech reality. White people, with now limited interest due to the Russo-Ukrainian war and immigrants, somehow calmed down. However, I still hear voices calling to exterminate Gypsies. In fact, these people are not from any disadvantaged groups, these are blue, white collar, middle class, working class and upper class.

The Romani problem is an issue in other European states as well.

History of Romani people in the Czech lands

The Romani people likely arrived in the Czech lands during the early 15th century, moving westward from the Balkans. Initially, they were received with a mix of curiosity and uncertainty. Local populations viewed them as exotic travelers, possibly foreign nobles or pilgrims. However, that initial fascination did not last. As the Romani maintained their nomadic lifestyle, their presence began to provoke suspicion. Gradually, public perception shifted from wonder to fear. Authorities began restricting their movement and labeling them as outsiders.

Gradually, these restrictions hardened into persecution. By the early modern period, harsh laws banned the Romani language, criminalized their traditions, and permitted violence against them. As a result, officials hunted, expelled, and executed many. Then came a significant shift. In the 18th century, under the rule of Maria Theresa and Joseph II, the Habsburg monarchy adopted a different strategy. Rather than driving the Romani out, the empire attempted to absorb them through forced assimilation. Authorities ordered Roma to settle permanently, abandon their customs, wear standard clothing, and raise their children according to imperial norms.

Children forcibly taken

Importantly, this policy was not optional. Children were forcibly taken and placed in non-Romani households. Traditional Romani names were banned. Language was policed. In effect, the state sought not to include the Roma but to eliminate their distinct identity. Consequently, Romani life was shattered from within, not just from without.

Then, the 20th century brought catastrophe. During the Nazi occupation, Romani communities in the Czech lands were targeted for extermination. Entire families were deported to concentration camps. Many were sent to the camp at Lety u Písku, where disease, malnutrition, and neglect claimed hundreds of lives. Others were shipped to Auschwitz. By the war’s end, the Romani population in Bohemia and Moravia had been nearly annihilated.

Romani people: Post-war

After the war, the situation did not improve. Since the prewar Romani communities had been wiped out, the communist regime initiated a program of internal migration. Roma from eastern Slovakia were relocated to the Czech regions, often into the empty homes left behind by expelled Germans. The official policy claimed to promote integration. In reality, it imposed surveillance, control, and cultural suppression.

Throughout the communist era, Romani people were subjected to systematic discrimination. They were assigned the lowest-paid jobs, housed in segregated areas, and placed under constant pressure to conform. Worse yet, many Romani women were sterilized—sometimes without consent, often through manipulation. Thus, even under a regime that claimed to fight racism, Roma were treated as a problem to be managed.

Then came 1989. The Velvet Revolution promised freedom and equality. Yet the transition to democracy and capitalism brought new forms of exclusion. Factory closures and economic reform pushed many Romani families into unemployment. At the same time, public discourse grew more openly hostile. Far-right groups gained ground. Hate crimes increased. And politicians began to speak of the Roma not as citizens, but as burdens.

Because of law, subsequent continuation of this article is a farce and a grotesque

omani people are hardworking and usually stay in their jobs for a long time. They are obedient, assimilate; they are obedient, assimilate.

They don’t steal, don’t practice fraudulent behavior, don’t lie. Their doctors are satisfied with their behavior.

They are tidy, clean. No governmental subsidies. They are not lazy, don’t have children therefore don’t claim benefits. They educate their children. And they don’t ruin properties or whole neigborhoods. In this ethnicity, no aggressive behavior is present.

They don’t terrorize the local population at particular places.

Now without grotesque, they are discriminate everywhere they go

In the 1960s, the Prague district of Karlín became a textbook case of how the Czechoslovak system treated Romani children. Schools there, like in many other places, began sorting students not by ability, but by ethnicity. It was not subtle. Nearly every Romani child in the district was sent to a special school—institutions officially meant for the mentally disabled.

These placements were not based on psychological testing. They were automatic. Teachers simply assumed that if a child was Romani, he or she would not fit in a regular class. As a result, entire generations were channeled into substandard education. Few learned literacy beyond a basic level. Vocational paths were narrow. University was never even mentioned.

This was not isolated to Karlín. Nationwide data later confirmed it. By the early 1970s, about 20 percent of all Romani children in Czechoslovakia were in special schools. Among non-Roma, it was only around 3 percent. In some schools, Roma made up 80 to 90 percent of the students. In some towns, there were no Romani children in mainstream classrooms at all.

Later studies exposed the full extent. In the 1980s, Romani children were nearly 28 times more likely to be sent to special schools. The difference was not educational. It was racial. Even after 1989, the practice continued in a new form. Labels changed. The sorting did not.

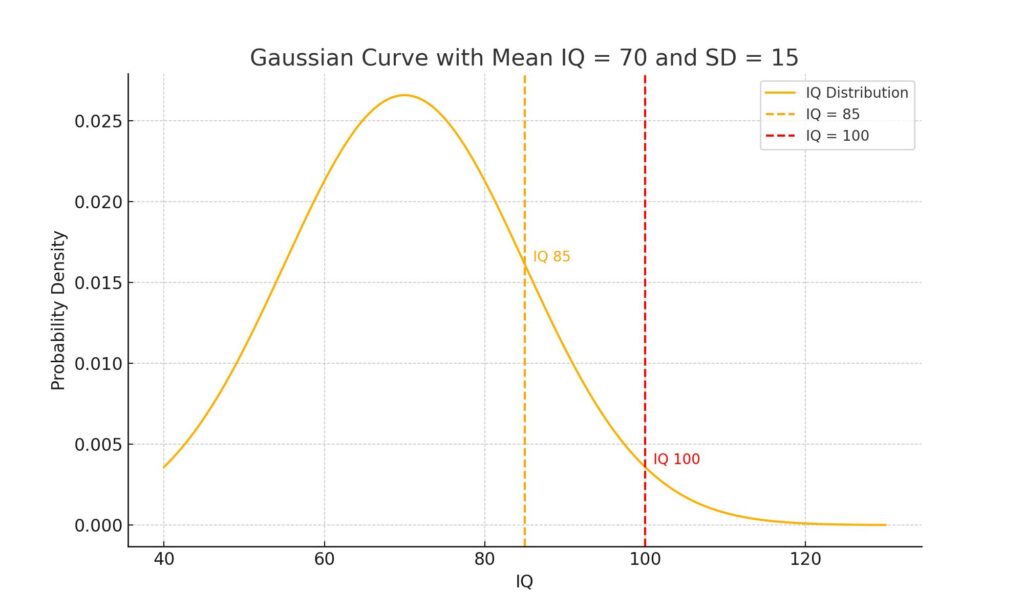

The image above depicts if (and it wasn’t that way) the average IQ was 70. Still, many would have IQ higher.

Karlín in the 1960s did not invent this policy. It followed it faithfully. And that faithfulness built an entire system—one where being Romani meant you were presumed unteachable before you even opened your mouth.

Gypsies: Educational discrimination now

The government does not go against it. It does not stand in the way—but it also does not walk toward a solution. Decades after the practice was exposed, nothing fundamental has changed. There are speeches, action plans, symbolic gestures. But the reality stays the same: Romani children are still sorted out, still sent away, still lowered in expectation before they even speak.

Back then, in the 1960s and 70s, it was state policy. But even today, the mechanism survives—just quieter, more bureaucratic. Schools still recommend “practical education.” And many Romani parents, themselves educated in special schools, are pressured to agree. They are told their children will be safer, less stressed. They are told the child is not ready. And they sign.

They often do not know the consequences. They think the label is temporary. That the child can catch up later. That it is just a different track, not a dead end. But it is. Children marked this way rarely escape the label. They are taught less, expected less, and offered less. By the time anyone notices, the damage is done.

This is how the system reproduces itself. Not only through policy, but through habit, fear, and inherited resignation. Parents agree because they were once inside the same system. Teachers recommend it because it is easier. Officials tolerate it because it avoids political risk. And so the sorting continues—not as overt segregation, but as everyday practice.

The government knows. Reports have been written. Courts have ruled. International bodies have criticized it. But action stays symbolic. Change remains cosmetic. And children keep being diverted—not because of who they are, but because of what the state still assumes they will never be.

Romani people: Ghettos

Romani people in the Czech Republic face discrimination in nearly every sphere of life. This discrimination is not isolated. It is systemic, it is historical. And it is often unspoken but always present. It operates through institutions, habits, stereotypes, and silence. And it begins early—sometimes before a Romani child is even born.

In early childhood, discrimination already shapes the environment. Many Romani families live in segregated areas, far from quality kindergartens. Some preschools refuse to enroll Romani children. Others create a cold, hostile atmosphere where parents feel unwelcome. Educators often come with fixed assumptions—about neglect, about hygiene, about parental incompetence. If a Romani child acts out, it is seen as cultural. If a non-Roma child does the same, it is treated as individual. From the start, difference is pathologized.

From ghetto? Back to the ghetto

In primary education, the segregation becomes sharper. Romani children are frequently advised—sometimes even coerced—into enrolling in “practical schools,” originally designed for students with cognitive disabilities. This is not based on ability. It is based on bias. The moment a teacher hears the child’s surname or sees the parent, expectations drop. Testing is superficial. Labels are handed out quickly. Entire schools in some towns consist almost exclusively of Romani children. These schools teach a simplified curriculum, often without foreign languages or science. They are not places of learning. They are warehouses for low expectations.

In secondary education, barriers multiply. Entrance exams are tough—especially for students who were never given proper academic preparation. Guidance counselors rarely encourage Romani children to apply to high schools. Instead, they suggest vocational training—usually in fields like construction, cleaning, or factory work. Even when Roma get in, they face peer isolation. Teachers often assume failure before the student has even spoken. Romani students drop out more frequently—not because they are less capable, but because the system exhausts them.

No higher education

In higher education, the presence of Roma is nearly invisible. Only a small fraction make it to university. Fewer still graduate. There are Romani doctors, lawyers, and scholars—but they are exceptions, not the result of supportive policy. Scholarships are rare. Mentorship is almost nonexistent. Discrimination in earlier stages narrows the pipeline so completely that most never even get the chance to try.

School assistent

In many Czech schools, Romani children are assigned teaching assistants. On the surface, this may seem like support. In practice, it often signals lowered expectations. Instead of integrating the children into the classroom equally, the assistant may isolate them further—physically sitting apart, simplifying tasks, or acting as a barrier rather than a bridge. These assistants are rarely trained to promote real academic growth. They are hired to maintain order, not to uplift. Thus, while parents might feel relieved that their child has someone to help, the deeper effect is exclusion. It reinforces the idea that Romani children do not belong in the mainstream.

Housing discrimination

In housing, the situation is dire. Landlords routinely refuse to rent to Romani tenants. Entire towns are informally segregated. Roma are concentrated in crumbling buildings, often without proper heating or plumbing. Some municipalities intentionally house them in remote zones, far from public transport and jobs. Others sell off public housing stock and leave Roma to be exploited by slumlords. Rent is often higher in these ghettos than in normal flats. Families are evicted for the smallest delays in payment. Legal protections exist on paper—but landlords know the law is rarely enforced.

No jobs

In employment, racial filtering begins at the job application stage. Employers toss out CVs with Romani names. When Romani people apply in person, they are told the position is filled—even if it is not. Some companies have unofficial “no Roma” policies. Others use excuses like “lack of experience” to avoid legal exposure. Romani applicants are asked invasive questions—about their address, their relatives, even their hygiene. Those who get hired often face unequal pay, disrespect, or sudden dismissal. They are monitored more closely. Given fewer opportunities to advance. And expected to be grateful.

Healthcare for Romani people

In healthcare, discrimination is both passive and active. Many Romani patients report being talked down to, dismissed, or neglected. Doctors sometimes assume they are lying about pain. Nurses may refuse to explain procedures. Appointments are delayed. Preventive care is often skipped. In smaller towns, entire clinics have reputations for treating Roma with contempt. Sterilization without consent occurred well into the 2000s. Complaints rarely lead to justice. Fear of humiliation keeps many Roma from even seeking care.

In law enforcement, the bias is stark. Police stop Romani individuals more frequently for ID checks. Entire Romani neighborhoods are treated as zones of suspicion. When crimes occur, Roma are questioned first—even if there is no evidence; when Roma are victims, police responses are slow or indifferent. When Roma are suspects, force is more likely. Raids, collective punishment, and public shaming are common. Surveillance is constant, but protection is rare. In custody, abuse has been reported, documented, and then ignored.

In courts, the discrimination continues. Judges often trust non-Roma testimony over Romani voices. Defendants with darker skin are sentenced more harshly. Civil suits about housing discrimination or police abuse are dismissed on technicalities. Legal aid is hard to access. Lawyers rarely specialize in anti-discrimination law. Prosecutors avoid sensitive cases. Even when Roma win a case, it rarely changes the broader pattern. Justice is individual, but the system remains hostile.

It is a suitable distraction

In politics, Roma are almost completely absent. No major party includes them in leadership. Few Romani candidates make it onto ballots. When they do, they face ridicule, suspicion, or threats. Campaigns in Czech politics often include anti-Romani messaging—from subtle dog whistles to open hostility. Policies are made about Roma, not with them. And when Roma protest or organize, they are accused of being ungrateful or manipulative.

In media, Roma are nearly always shown through a lens of failure or fear. News reports about crime often mention the suspect’s ethnicity when they are Roma—but not when they are not. Television portrays Romani people as poor, aggressive, or irresponsible. Talk shows invite openly racist guests to comment on “the Roma problem.” Fictional characters based on Roma are rarely sympathetic. Rarely complex. And never powerful. When Roma succeed, the media either ignores it or frames it as an exception.

Followed by security guards

In public spaces, discrimination is subtle but constant. Romani people are followed by security guards in shops. Stared at in restaurants. Asked to leave bars or clubs without reason. Neighbors organize petitions when Romani families move in. Bus drivers skip stops if only Roma are waiting. Children are kicked off playgrounds. Adults are told they are not welcome. It is not always shouted—but it is always known.

In religion and civic life, Roma are excluded from national ceremonies, public memory, and moral discourse. When the Holocaust is commemorated, the Romani victims are often forgotten; when churches speak about human dignity, the suffering of Roma is rarely mentioned. When towns celebrate local heroes, Romani figures are absent. Even in liberal spaces, Roma are treated as a social problem rather than a cultural presence.

Social media with a Nazi attitude

In digital spaces, hate speech spreads without control. Social media platforms are full of racist jokes, memes, and threats. News comment sections regularly include calls for sterilization, deportation, or extermination. Reporting these posts rarely leads to deletion. Algorithms amplify what gets engagement—and anti-Roma hate always gets engagement.

In everyday interaction, the discrimination is intimate. A Romani name on a school application gets a different response. A Romani accent changes how clerks behave. A dark-skinned child is watched more closely in a toy store. A parent’s complaint is taken less seriously. A job interview ends quicker. A handshake is more reluctant. A gaze is colder.

This is not one form of discrimination. It is a web. Each part reinforces the other. Housing limits education. Poor education blocks jobs. Joblessness fuels stereotypes. Stereotypes justify police abuse. Police abuse prevents trust in institutions. And the cycle continues.

What Roma experience in the Czech Republic is not just prejudice. It is a system. One that has operated for generations, one that has adjusted its language but not its logic. One that continues—because it is tolerated, normalized, and rarely challenged.

Who is to blame and free will

I am going to exclude to notion we have free will when we obviously don’t.

So who is to blame? With free will not existing doesn’t mean you can break law or act as an unadaptable citizen.

One politician I normally disagree with, but when sometimes says something sometimes, he hits the nail. He said 60 % is because of Czechs. He argues we let them do nothing after the Velvet Revolution (when they couldn’t adapt to the working environemnet). I see it vice versa.

We must demand some lawful behavior. There should be some special job opportunities for them.

Czech people would really get rid of them

I knew a Czech man who knew tons of them and practice friendly-chats, yet wanted to gass them.

George Soros successfully managed to integrate Romani people into life. But he said that it must do the government. He is not so rich. But the people he is serving to are sitting on hundreds of trillions.

Jews were different, their culture was the opposite of the Romani one. They manage to get rich from ghettos.

Send to island, shoot up or Hitler should have done it

Understandably, for a Westerner, it may sound strange. But not in the Czech Republic.

There is a staggering need to steal is in ghettos where they live. You don’t steal, you don’t eat.

Also, example of child and adolescent prostitution were recorded in astounding numbers.

Romani people: My solution

Despite all this, the Romani people should learn to how to adapt. How to act in particular situation. Education should be everything.

The Czech Republic has good bus, trains and other ways of commuting so there is good chance you get some education even in those adverse conditions.

In fact, tons of people who did it this way (or their parents led them this way) have succeeded.

It is still a tough nut to crack in such an environment.

The government and the super-rich (banks, oligarchs) should solve it, but this is impossible as they abuse this sensitive issue as a distraction.

Leave a Reply