The Czech Republic is officially a republic, but many treat the president as if he were a king. People project onto him a ceremonial aura, as though the office itself carried divine or hereditary weight. Citizens expect him to embody the national spirit, deliver moral guidance, and act as a symbol rather than simply a public servant. This transforms an elected official into a quasi-monarch, a figure treated with deference that has no place in modern democracy.

The presidential castle, ceremonies, and symbols only deepen this illusion. The nation imagines that it needs a father figure in office, when in reality, democracy demands officials who are accountable and replaceable. Czech presidents often enjoy more respect than parliament, courts, or ministries. That is not because they are more competent, but because they inherited an aura that once belonged to kings. They represent not only a living politician but also the shadow of an ugly history rooted in monarchic rule.

Enormous influence and wealth

Royals across the world hold fortunes worth billions, sometimes trillions. These were not earned through merit, but accumulated through conquest, colonialism, and dynastic exploitation. They live in palaces while ordinary citizens face poverty, and they use their wealth to shape politics. They fund parties, hire lobbyists, and buy media narratives. Their presence distorts political systems and maintains hierarchies that should have been dismantled long ago.

Even in republics, leaders absorb influence that goes beyond their constitutional role. Czech presidents, for example, use their symbolic power to pressure governments, push their allies, and cultivate clientelist networks. This influence is dangerous because it is hidden under the mask of ceremonial duty. Whether through inherited assets or accumulated prestige, royals and their republican counterparts bend politics to their will.

Case study: The British monarchy

The British royal family illustrates the problem with clarity. They claim to be only ceremonial, but their influence and wealth are extraordinary. The monarch meets the prime minister every week and receives government papers before parliament does. The royal household secretly lobbies to shape laws in its favor, while the family enjoys immunity from many forms of scrutiny.

The financial side is equally striking. The Duchy of Lancaster and the Duchy of Cornwall provide the royals with enormous income. Their estates stretch across Britain, while their assets are officially valued in the tens of billions. Official ceremonies such as the queen’s funeral or King Charles’s coronation cost taxpayers hundreds of millions—paid during a cost-of-living crisis when citizens struggled to heat their homes.

The royal image is marketed as “tradition” and “unity,” yet scandals reveal its true nature. Prince Andrew’s ties to Jeffrey Epstein exposed corruption and moral bankruptcy. Meghan and Harry’s conflicts with the palace showed how the institution protects its image above truth. Far from being harmless, the British monarchy is a dynasty with enormous wealth, cultural dominance, and the ability to steer politics without ever standing in an election.

What royals and quasi-royals do not bring

Despite their wealth and prestige, they do not bring solutions to real problems. They do not produce innovation. They do not guarantee fairness, equality, or moral authority. Their symbolic roles are hollow, and those roles could easily be performed by officials without inherited privilege.

In Czechia, the “royal aura” around the president distracts from the institutions that actually matter. Courts, ministries, and parliament carry the burden of governance, yet citizens look to the president as if he were a king with answers. This illusion makes democracy weaker because it shifts attention away from accountability and toward empty spectacle.

What they do wrong

Royals drain public funds while jealously guarding dynastic wealth. Presidents exploit ceremonial prestige to build influence far beyond their mandates. Both cultivate clientelism and corrupt ties to business. Instead of balancing power, they reinforce inequality and entrench hierarchy.

This creates a twofold problem. Royals keep their dynasties alive by maintaining ancient privilege. Presidents keep the illusion alive by acting as little kings, using castles, rituals, and rhetoric to cultivate obedience. In both cases, the public is manipulated into reverence for individuals who do not deserve it.

The ugly masquerade

Ceremonies, processions, and royal weddings are not displays of unity. They are theater. The theater hides the fact that both royals and presidents act as symbols of privilege. The castle becomes a stage, the office a costume, and the people an audience forced to applaud.

Citizens reward mediocrity with respect only because of the costume. They confuse symbols for substance, authority for competence. The masquerade works because it plays on human weakness: the desire to follow leaders who look majestic rather than those who govern well. And when presidents inherit the aura of kings, the masquerade becomes an echo of a darker past.

Who should rule instead

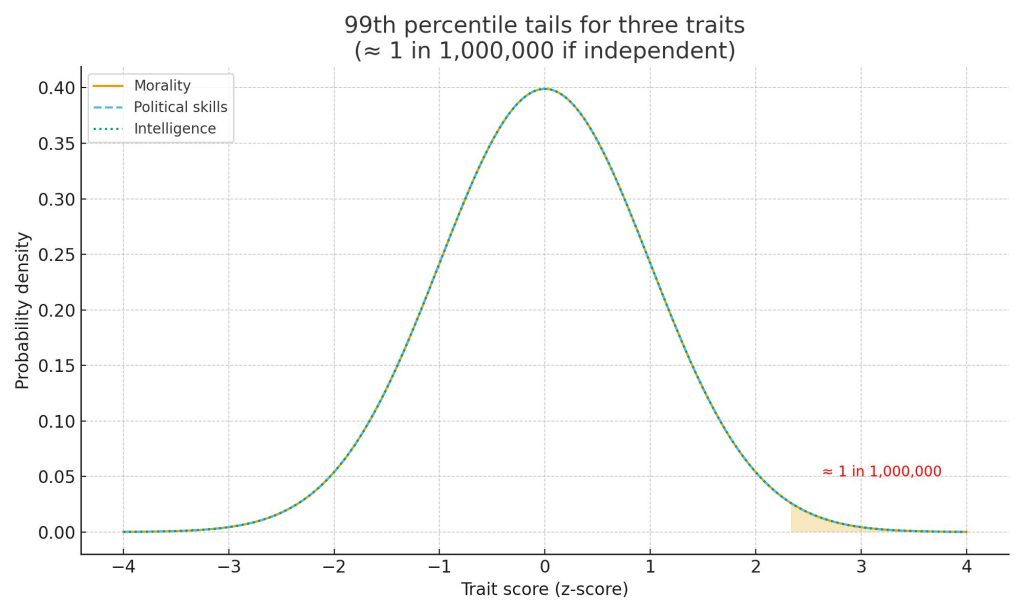

Power should not belong to dynasties, nor to presidents who act as kings. It should belong to people chosen on the basis of merit. Imagine 100 citizens elected not because of their family name, but because they stand at the 99th percentile in political skill, morality, and intelligence. These leaders would represent the very best of society.

Their collective power would prevent any single individual from turning into a monarch. A council of the best minds would replace feudal inheritance and ceremonial authority with measurable excellence. Such a system would not only be democratic but also rational, because leadership would rest on skill, not on bloodlines or hollow symbols.

Media as constant oversight

Yet even the best leaders require scrutiny. Power corrupts, and without transparency, even the most intelligent council could turn clientelist. That is where media comes in. Journalists must investigate constantly, exposing hidden ties, revealing corruption, and tracking failures.

But oversight should not stop there. One newspaper might expose a leader’s clientelist ties. Another might then expose whether that newspaper itself is compromised by hidden interests. This chain of exposure keeps the system alive. Everyone watches everyone else, and no one can hide behind privilege. Royals cannot survive in such light. Neither can little kings in castles.

Conclusion: Ending royals and fake kings

Monarchs and quasi-monarchs thrive on wealth, influence, and theater. They pretend to serve the people while serving only themselves and their dynasties. Their influence is not symbolic—it is political and economic, shaping laws and markets from behind the curtain.

True republicanism demands an end to this illusion. Leaders must be officials, not dynasties or figures wrapped in medieval symbols. They must be accountable, replaceable, and chosen for excellence. With 100 leaders drawn from the top percentiles and with relentless media oversight, society could finally move beyond kings, queens, and castle presidents. Equality requires it. Democracy requires it. And the future will not wait.

Leave a Reply