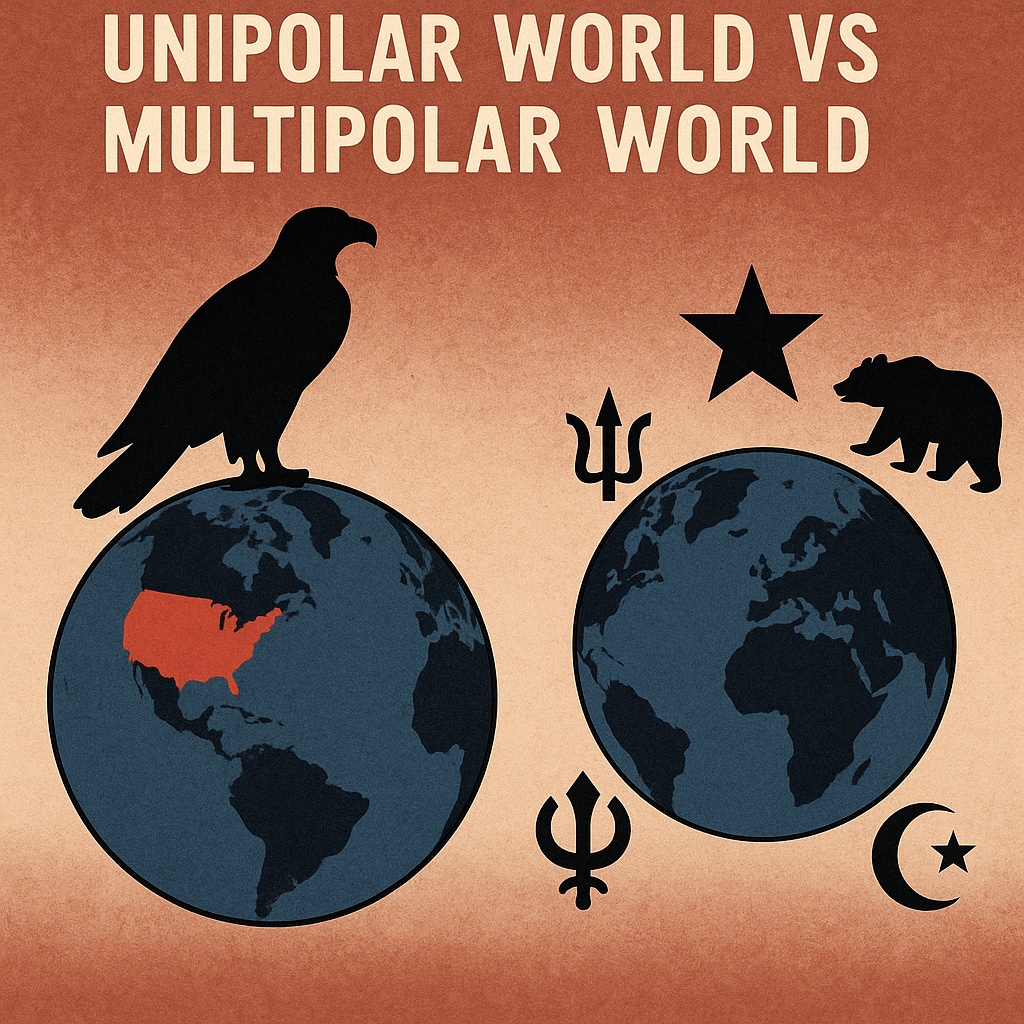

Global power never stays frozen. It shifts with economic growth, military strength, and cultural influence. At the highest level, there are two basic shapes of the world order. A unipolar world has one dominant power setting the rules. A multipolar world has several major powers competing and cooperating. History has seen both—and each brings its own risks and rewards.

The rise of the unipolar world

After the Cold War, the United States stood alone as the dominant superpower. Its military could project force to any corner of the planet. The dollar became the world’s reserve currency. International institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, and NATO largely reflected U.S. interests.

In this unipolar system, the wealthy Global North—especially Western powers—set the rules of trade, credit, and development. Institutions like the IMF and World Bank pushed Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs): loans conditional on privatization, austerity, and liberalization. These conditions often devastated health systems, education, and public infrastructure across Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

Developing nations now face roughly $29 trillion in public debt—nearly 30% of all global debt, up from 16% in 2010. High borrowing costs force countries to spend more on servicing interest—sometimes up to 14% of domestic revenue—instead of investing in public goods. Most of these loans must be repaid in U.S. dollars, locking countries into dependence on the Western financial system.

Natural resource exploitation reinforces the cycle. Many resource-rich countries export oil, gas, or minerals but remain underdeveloped because extraction profits flow to foreign corporations and local elites. Politicians and shadow power brokers benefit from the status quo, ensuring it remains intact. Under unipolarity, these nations cannot chart independent economic paths; debt, dollar dependency, and resource exploitation keep them in permanent subordination.

Unipolarity had strengths—one set of rules brought predictability in trade and diplomacy, and a single leader could respond to global crises quickly. But it also concentrated power in dangerous ways, letting the United States and its allies maintain global dominance while the Global South bore the structural costs.

The emergence of multipolarity

In the 21st century, the U.S. grip weakened. China’s economic rise, Russia’s military resurgence, India’s growing influence, and regional powers like Brazil, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia began to challenge the old order. BRICS formed as a counterweight to Western dominance.

Multipolarity brings more balance. No single country can dominate the rest. Smaller states gain the option to work with multiple partners. Yet multipolarity also complicates decision-making. Conflicting alliances can paralyze international action. Rival powers may turn competition into proxy wars, creating instability rather than peace.

Economic dimensions

Unipolarity kept the dollar as the global standard. U.S.-controlled systems such as SWIFT reinforced this dominance. Multipolarity challenges that. China promotes its yuan for international trade. Regional trade deals bypass the U.S. entirely. Alternative payment systems like CIPS emerge.

For developing countries, the shift cuts both ways. Unipolarity meant dependence on Western loans and markets. Multipolarity offers more investment sources—but also more debt traps and conflicting terms.

Military and security implications

A unipolar security model lets one dominant power guarantee stability—at least in theory. U.S.-led alliances acted as global police. In practice, this often meant wars without broad consensus.

Multipolar security is more fragmented. Regional powers build their own alliances and arm themselves against each other. This spreads risk but also increases the chance of local conflicts escalating. History offers examples: the 19th-century balance of power in Europe avoided major war for decades but failed catastrophically in 1914.

Information and cultural power

Under unipolarity, U.S. culture dominated global media. Hollywood, Silicon Valley, and American universities set trends and framed debates. Multipolarity erodes this monopoly. Chinese tech platforms, Russian media outlets, and regional cultural industries compete for global attention. The battle for soft power becomes as intense as the contest for markets and territory.

Historical parallels

History shows repeated shifts between unipolar and multipolar systems. The Roman Empire was a unipolar order in the Mediterranean—its dominance brought stability but also bred complacency and eventual overreach. After its collapse, Europe fell into a multipolar Middle Ages, where rival kingdoms and empires competed endlessly, often through war.

The early 19th century’s Concert of Europe was multipolar, with Britain, France, Austria, Prussia, and Russia balancing each other to prevent Napoleon’s return. This worked for decades but failed when nationalist movements and imperial ambitions outran diplomacy.

The post–World War II world was bipolar—the U.S. and the Soviet Union dominated their respective blocs. The end of the Cold War created a brief unipolar moment for the U.S., resembling Britain’s 19th-century imperial dominance, but on a global scale. Both cases show that unipolarity can last only as long as economic and military supremacy is unchallenged.

These cycles suggest that neither system is permanent. Economic rise and technological change eventually shift the balance, forcing transitions that are often turbulent.

Competing views: Kissinger vs Rothkopf and beyond

Henry Kissinger warned that unipolarity would not last. He urged the United States to prepare for multipolarity, not resist it. His model drew from the 19th-century Concert of Europe—great powers balancing each other through diplomacy, mutual respect, and restraint. For him, multipolarity could stabilize the system if its members respected order. Without that, he saw chaos ahead.

David Rothkopf took the opposite view. He argued that U.S.-led unipolarity gave the world its best shot at stability. In his eyes, the United States alone could enforce a rules-based order. Multipolarity, he said, meant paralysis in crises, more regional conflicts, and the breakdown of global norms.

John Ikenberry leaned toward Rothkopf but set conditions. He saw U.S. primacy as effective only when tied to strong multilateral institutions. He warned that dominance without self-restraint or institutional limits would undermine the very system it built.

Stephen Walt saw unipolarity as unstable. Without balancing powers, the hegemon would overreach. He favored a soft multipolar order—several powers checking one another without constant war. Clinging to unipolarity too long, he warned, would trigger a backlash.

Fareed Zakaria foresaw a “post-American world” driven by the rise of other powers. He did not predict U.S. collapse, only relative decline. In his view, the United States would remain strong but would need to share influence. Multipolarity, if managed well, could work.

Graham Allison looked at history and saw danger. Power transitions often ended in war. His “Thucydides Trap” warned that rising powers challenge ruling ones, and the U.S.–China rivalry would test if this shift could stay peaceful.

Samuel Huntington predicted that cultural blocs, not just states, would weaken U.S. dominance. He saw unipolarity as temporary, with civilizational rivalry replacing ideological confrontation.

Brzezinsky, Chomsky, Nye

Zbigniew Brzezinski supported U.S. primacy but cautioned against arrogance. He believed that mishandling Eurasian politics would speed the rise of rivals.

Noam Chomsky dismissed the idea that unipolarity served the common good. He saw it as empire with democratic branding. For him, multipolarity at least gave space for competing powers to limit one another.

Joseph Nye argued that U.S. unipolarity could last longer if it relied on attraction instead of force. He believed future power would depend on networks of influence as much as armies or GDP.

Christopher Layne predicted that unipolarity would provoke balancing coalitions. The harder the U.S. tried to preserve dominance, the faster it would lose it.

Paul Kennedy reminded readers that no hegemon escapes the trap of “imperial overstretch.” He argued that economics, not war, would force the U.S. into a multipolar world.

Robert Kaplan warned that multipolarity could be more violent than unipolarity. He looked to the years before World War I as a lesson in how competing powers stumble into disaster.

Kishore Mahbubani welcomed multipolarity. He argued that Asia’s rise was unstoppable and that the U.S. could either share power or watch the system fracture.

These voices show more than a split between unipolar and multipolar preferences. They reveal a deeper divide—between those who see change as a chance to build a new order and those who see it as a threat to stability. The question is not if the order will shift, but how, and at what cost.

Global dimension: the racket without borders

Neither unipolarity nor multipolarity automatically serves the public good. Both can be hijacked by elites. A unipolar hegemon can use its dominance to enforce its own interests globally. In a multipolar world, several elites do the same within their spheres of influence. The difference is in who holds the stick, not whether the stick exists.

Conclusion: choosing a global future

The world is shifting toward multipolarity. That shift brings a chance for more balanced power—but also for greater instability. The ideal is a cooperative multipolarity where states share leadership and resolve disputes without war. The danger is a chaotic one where rival blocs harden and smaller nations become battlegrounds.

Whether unipolar or multipolar, the real challenge is preventing the system from turning into a tool for the few at the expense of the many. Without that, the shape of the world order matters less than the fact that it remains a racket.

Leave a Reply