Every single US voter is fully aware that there are tens of patron-client networks ridden through American politics that grossly disrupt the process detrimental to every citizen. So he or she daily reads media based on information from the political background devoid of our prehistoric like of story-telling. Just statistics and mathematics. No campaign, just reading plain texts, life-long learning how to vote, no TV, social media, or newspaper ads. He chooses such parties that are devoid of clientelism, and internal feuds and are working together to improve voters’ well-being. Wrong! Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to The Political Circus. This quote (the title) is attributed to German chancellor Helmut Schmidt: The biggest problem in politics is the stupidity of people.

How emotions play a role in politics

Politicians emotionally influence people through a combination of carefully crafted messaging and political marketing that taps into their deepest feelings. They understand that emotions, more than facts, drive human behavior, and they use this to their advantage. Fear is a powerful tool in this playbook. Politicians highlight threats, whether from economic instability, immigration, or crime, to create a sense of urgency and danger. This triggers an instinctive need for protection, leading voters to support candidates who present themselves as the solution to these fears. When people feel insecure, they look for leadership that promises safety and stability, even if the threats are exaggerated.

At the same time, politicians know how to tap into hope. By offering visions of a brighter future, they inspire voters who crave change or improvement. Campaigns use hopeful slogans and imagery to make voters feel that their lives will get better under a particular candidate’s leadership. This emotional appeal to optimism resonates deeply, particularly during times of economic or social challenges. Political marketing amplifies this effect, with ads, speeches, and social media posts designed to stir positive emotions and make voters feel connected to the candidate’s vision.

Identity and manipulation

Identity also plays a critical role in emotional influence. Politicians craft their image and rhetoric to align with specific groups. This makes voters feel that the candidate represents their values and experiences. Whether it’s through shared cultural, religious, or national identities, politicians create emotional bonds that go beyond policy and facts. This appeal to identity is heightened by political marketing, which uses targeted messaging to speak directly to different voter demographics, making each group feel personally seen and represented.

Political campaigns are designed to manipulate these emotions at every turn. It’s not about presenting voters with balanced information. It’s about triggering feelings that will secure loyalty. Political ads, debates, and social media campaigns are all focused on stirring emotions, whether it’s anger, pride, hope, or fear. Voters aren’t just choosing policies – they’re choosing based on how a candidate makes them feel. This emotional manipulation is at the heart of political marketing, turning elections into performances. The goal is to evoke the strongest emotional reaction, not the most informed decision.

The political circus: Fake smiles

Politicians often put on fake smiles during campaigns, a well-practiced performance meant to project warmth, confidence, and relatability. These smiles are part of the larger act of connecting with voters on an emotional level, even if the authenticity behind them is questionable. Campaigns are high-stakes, and candidates are coached to smile at the right moments. Whether shaking hands at rallies, delivering speeches, or posing for photos. The smile is a tool to make them appear approachable and trustworthy. Even when it’s a thin layer over stress, frustration, or indifference.

These smiles are carefully calculated. Politicians know that voters are more likely to trust and support someone who seems friendly and confident. So the smile becomes a powerful part of their image. Yet, the disconnect between a politician’s public smile and their private reality can be glaring. Behind closed doors, many are under enormous pressure, calculating political moves or dealing with scandals. But in front of the cameras, they flash a grin as if everything is perfect. The smile becomes a mask, used to hide the less pleasant realities of political life.

During campaigns, these rehearsed expressions are everywhere – on TV ads, in debates, and during public appearances. The smile becomes almost robotic, more a performance than a genuine reaction. It’s part of the political theater that candidates rely on to win votes. And while it may succeed in softening their image, it often lacks the sincerity that voters crave. Still, in the world of political marketing, a well-timed smile can make or break a candidate’s image. Even if it’s not a true reflection of what they feel.

The matter of fact is that people’s choices shouldn’t be dictated by primitive emotions at all.

The biggest problem in politics is the stupidity of people: So we have political marketing

Political marketing is a sophisticated field that operates much like commercial marketing, but with the goal of influencing public opinion, mobilizing voters, and winning elections. The foundation of any effective political marketing campaign is audience segmentation. This involves dividing voters into specific groups based on shared characteristics such as demographics – age, gender, location, or income – and psychographics, which includes values, beliefs, and interests. By breaking down the electorate into these segments, campaigns can tailor their messaging to meet the specific needs and concerns of each group. Data collection plays a critical role here. And campaigns rely on polling, surveys, social media analytics, and voter databases to gather the necessary information to effectively segment the audience.

Once voters are segmented, political campaigns begin tailoring their messages for maximum impact. For instance, younger voters might be more responsive to messages about climate change and student debt, which are delivered through social media platforms they frequently use. In contrast, older voters might respond better to messages about healthcare and social security. This is delivered via traditional media such as television and radio. The strategy extends beyond demographics; behavioral segments based on voting habits (like swing voters or consistently partisan voters) also influence how a campaign communicates with certain groups. Moreover, psychographic segmentation allows campaigns to address ideological concerns, such as tailoring specific messages for environmentally conscious voters or religious groups. This process ensures that campaigns do not waste resources on generalized, ineffective messaging but instead craft specific appeals that resonate deeply with voters.

Political branding

Political branding is another key aspect of marketing. Like product branding, political branding involves creating a persona or image that evokes emotional connections with voters. A strong political brand can shape how voters view a candidate beyond their policies. For instance, Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign successfully branded him as a candidate of “hope” and “change”. This resonated with voters eager for a fresh perspective after years of political disillusionment. Similarly, Donald Trump’s brand as a political outsider who would “drain the swamp” was appealing to voters frustrated with the political establishment. Branding also helps differentiate candidates from their opponents and position them in ways that directly appeal to the needs and frustrations of particular voter segments.

A robust media strategy is essential in any political campaign and works hand-in-hand with audience segmentation. Different voter segments consume media differently, so campaigns must choose the right platforms to reach their target audience. Traditional media, such as TV and radio, remain crucial for reaching older or rural voters, while digital marketing on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and X is increasingly critical for younger voters. Digital platforms allow for micro-targeting – using data to craft specific messages for small, defined groups of voters. Campaigns analyze voters’ online behavior and deliver ads that speak directly to their interests and concerns, whether through social media posts, emails, or video content. This data-driven approach allows campaigns to maximize efficiency by targeting undecided voters or reinforcing support among loyal segments.

Psychology of political marketing

The psychology behind political marketing also plays a significant role. Campaigns use emotional appeals – such as fear, hope, and anger – to drive voter behavior. For instance, fear-based messaging might highlight threats like terrorism or economic instability to trigger an emotional response, pushing voters toward a candidate positioned as a protector. Hopeful messaging, on the other hand, often paints a positive future, motivating voters to support a candidate who promises to bring about the change they desire. These emotional strategies are powerful because voters often make decisions based on their identity and feelings, rather than pure rationality. Political marketers understand that the way a candidate makes voters feel is as important as the policies they propose.

Moreover, political marketing doesn’t stop on election day. Post-election marketing is equally crucial for maintaining voter support and building a relationship that lasts beyond a single election cycle. Campaigns continue to communicate with voters through newsletters, social media updates, and community engagement, ensuring that supporters remain loyal and mobilized for future elections. This is also the time to solidify a candidate’s legacy and maintain their brand’s relevance, particularly if they plan to run for re-election. Long-term engagement is essential for fostering trust and keeping voters invested in the political process.

Political marketing has evolved significantly, with campaigns now relying on data analytics and segmentation to make their outreach as targeted and efficient as possible. The ultimate goal is to influence voters by addressing their specific needs and emotional triggers, ensuring that campaigns can effectively mobilize their base, sway undecided voters, and ultimately win elections. By engaging voters on a personal level, political marketers help shape not only the outcome of elections but the entire political discourse that follows.

Voting for false messiah

People often vote for a false political messiah. They believe that a single leader can fix all their problems and bring sweeping change. These leaders present themselves as outsiders, promising to reform broken systems and offer simple solutions to complex issues. Frustrated voters, eager for hope and desperate for change, rally behind these figures without critically examining the feasibility of their promises. This blind faith can lead to disappointment and even disaster when the leader fails to deliver.

Obama and Chávez

Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign is an example of this phenomenon. He campaigned on a message of “hope and change,” promising to unite a divided nation and bring a new era of politics. Millions of Americans, weary from years of war and economic crisis, believed he could fundamentally change Washington’s corrupt and gridlocked system. However, despite his charismatic leadership and historic significance, Obama’s presidency faced many of the same challenges as his predecessors. The political system remained deeply divided. And many of the issues he promised to address, such as economic inequality and healthcare reform, saw only incremental progress. This left many supporters disillusioned.

Another example is Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. In the late 1990s, Chávez came to power by presenting himself as a champion of the poor. He had vowed to break the grip of the corrupt elite and redistribute wealth. His populist rhetoric and promises of economic justice resonated deeply with the nation’s struggling population. However, his policies ultimately led to economic collapse, rampant inflation, and widespread poverty, with Venezuela’s citizens suffering greatly under the weight of his failed leadership.

These examples show that while voters often look to political messiahs during times of crisis, the reality of governance is far more complex. Leaders, no matter how charismatic or well-intentioned, rarely deliver on all their grand promises. Voters who pin their hopes on a single figure to solve deep-rooted problems are often left disillusioned when the reality of political compromise and systemic challenges sets in.

Intrigues between the super-rich, their bankers, and politicians

Since the US is completely ruled by super-rich families and their bankers (Super PACs), they often find themselves with a big power play with the politicians seeking election.

Promising money, then change positions. Super-rich group A is in a bad relationship with group B, while group C can change the status, but the candidate must promise some gain for the group. Meanwhile, it will make group D hostile.

The person candidating against can change group D, so it prevents the first politician from reaching C, so he or she must make concessions with groups A and B, so they are not hostile.

When the president is to be reelected, he or she is trying to play around the groups so he or she can get enough money.

Media moguls, needless to say, are involved and, of course, are being influenced and are influencing.

The biggest problem in politics is the stupidity of people

This is a quote from the late German chancellor Helmut Schmidt. And he was right.

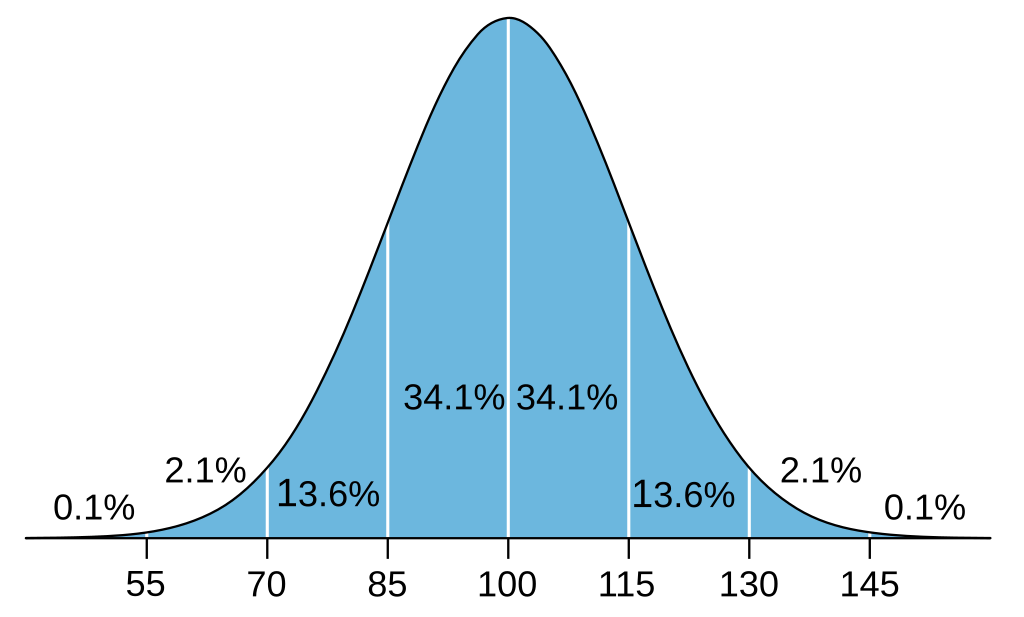

Another finding: A third of the people in the U.S.A. are feeble-minded. Every seventh citizen is either moronic, dementia-stricken, or an alcoholic. Half of the population has roughly below-average intellect. These people, half of the nation, are robbed of the world’s complicated multiformity, complementarity, and ambiguity, and an IQ of 100 is nothing.

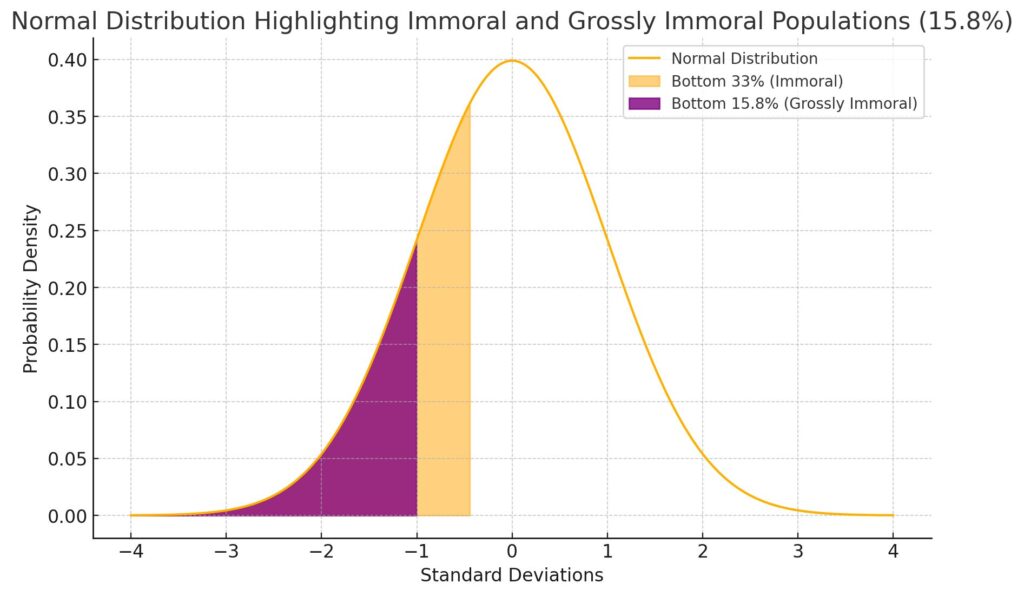

Half of the people (distributed by the Gaussian curve) are rather immoral, a third of people are sinful, around 15 % of people are deeply immoral, and 1 % are sociopaths.

Tell me, what kind of politics you should do? Exactly what they are doing.

The huge universe-like empathy of Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton, arguably one of the most talented politicians the US has (not to mention how many careers Clintons had destroyed), was often ascribed to a really good ability to empathize with people.

But what people? “The biggest problem in politics is the stupidity of people.” So I couldn’t have, were I at his place, concealed the truth. But that is the political circus.

Four or five non-negotiable issues. But you can buy us on everything else

In “Republic, Lost”, Lawrence Lessig discusses how lawmakers navigate their positions on various issues, explaining that only a small number of issues remain insulated from the influence of lobbyists. Specifically, Lessig suggests that on four or five issues, lawmakers are generally stable and cannot be easily influenced. However, for most other issues, the influence of lobbyists and special interests plays a major role, leading politicians to “sell their soul” to secure campaign funding and maintain political power. “The biggest problem in politics is the stupidity of people.”

The biggest problem in politics is the stupidity of people: Apathy and low-information voter

Apathy and low-information voters are two of the most significant challenges facing modern democracies. Apathy stems from the belief that individual votes don’t matter, that the political system is rigged or unresponsive. And that politicians are all the same. As a result, many people disengage from the process entirely, seeing no incentive to participate. This disengagement erodes the foundation of democratic systems, which rely on active citizen participation. Voter turnout decreases, and politicians are less accountable to the broader public, often catering only to their most engaged and financially supportive constituents. The cycle of apathy perpetuates itself as political corruption and unmet expectations discourage further involvement. This creates a system that only represents the interests of a narrow, elite group.

At the same time, low-information voters, those who make decisions based on limited knowledge of policies, candidates, or political issues, are highly susceptible to manipulation. Politicians, lobbyists, and media outlets exploit this lack of information, often relying on emotional appeals, catchy slogans, and superficial messaging to sway votes. Rather than engaging in critical thinking or seeking out in-depth information, low-information voters are often influenced by fear, identity politics, or the latest viral news stories. This leads to a distorted political landscape where decisions are driven more by emotion and rhetoric than by facts or policy analysis. As a result, elections can become more about marketing and less about meaningful debate, weakening the democratic process and allowing misinformation and demagoguery to thrive.

Dunning-Kruger effect a.k.a. I know everything

Another psychological bias frequently exploited is the Dunning-Kruger effect, where people with limited knowledge about a subject overestimate their competence and understanding. Politicians capitalize on this by simplifying complex issues into sound bites and slogans, making voters feel confident in their grasp of the subject despite their lack of depth. This oversimplification enables politicians to manipulate public opinion by presenting themselves as straightforward and relatable, offering seemingly easy solutions to multifaceted problems. The interplay of these biases allows political messaging to bypass rational debate and critical thinking, relying instead on emotional triggers and cognitive shortcuts. By tapping into these psychological vulnerabilities, politicians can effectively guide voters toward decisions based on feelings of certainty and identity rather than informed analysis, ultimately shaping public discourse and outcomes in ways that favor their agendas.

The long-term consequences of short-term thinking

Politicians, particularly in systems where elections happen every few years, are often incentivized to focus on short-term wins to secure votes rather than implementing long-term solutions to pressing issues. This short-term thinking leads to policy decisions aimed at quick, superficial successes rather than addressing deep-rooted problems like climate change, economic inequality, or healthcare reform. The constant cycle of campaigning forces politicians to prioritize optics and immediate gratification over sustainability, further perpetuating a dysfunctional system. If people were normal, even the politicians who voted for short-term would work for solutions that will last long.

The role of political spin doctors

Political “spin doctors” play a key role in managing how politicians are perceived by the public. These communication strategists craft messages to frame any situation in the most favorable light. Whether it’s downplaying a scandal, spinning poor economic performance into positive progress, or shifting the blame onto opponents. Spin doctors are masters at using the media to manipulate public perception, often flooding the news cycle with distractions when unfavorable stories arise. This constant manipulation of narratives contributes to the performative nature of politics, where perception becomes more important than reality.

It is not about people. It’s about big data

With the rise of big data, campaigns now use sophisticated algorithms and behavioral data to craft hyper-targeted political messages. Political strategists analyze millions of data points from social media, online activity, and consumer behavior to segment voters into micro-targeted groups. These groups receive customized political ads and messaging tailored to their specific fears, beliefs, or desires, often reinforcing their biases. This further entrenches polarization and ensures that voters hear only what they want to hear.

Echo chambers and filter bubbles

In today’s media landscape, people increasingly consume news and information from sources that align with their own beliefs, creating echo chambers. Social media algorithms exacerbate this by showing users content similar to what they’ve previously engaged with, filtering out opposing viewpoints. This strengthens confirmation bias and political polarization, as voters become trapped in filter bubbles where their opinions are continuously reinforced. Expanding on this idea could highlight how these bubbles make it easier for politicians to manipulate their base and harder for voters to access balanced information.

The political circus: A politician wears off

New, moral, huge expectations. But in politics, you are put into a constellation that one move can reset it all. So you must do things people don’t like. You have alienated interest groups and their media that go against you.

Scandals, bad politics (but necessary), and don’t forget this is not just a phenomenon of politics. A politician wears off. It same goes for the movie, music, or book industry.

Politicians would love to get rid of the shadow eminences, but…

Whether it is a crook, mover and shaker, lobbyist, super-rich family, and its owned banks, your average politician would like to get rid of them.

People, of course, even if the left-right wing spectrum was correct (which isn’t), vote against their interests.

There is always a messiah that will save us.

To my clever readers, I conclude this article with this sentence: “The biggest problem in politics is the stupidity of people.”

Leave a Reply