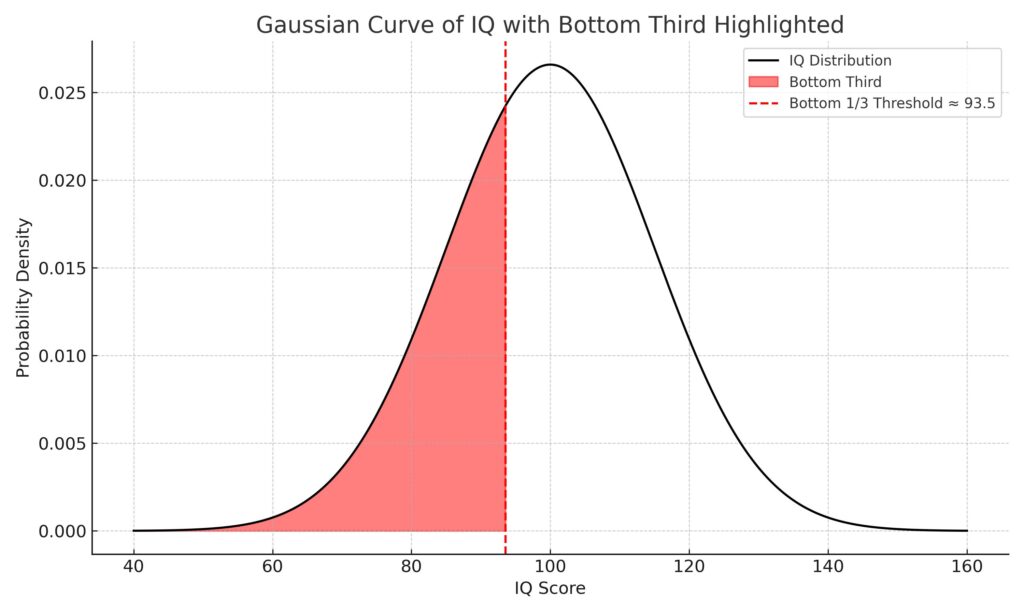

“Don’t be surprised at all. One third of Czechs are idiots!” This quote was proclaimed by one late prominent Czech psychologist. He also pointed out that IQ 100 is nothing. If we put aside how rude it was, he said nothing but the truth. Look at newspapers and magazines! Are they written for someone who has an IQ of 140 or your regular non-intelligent people?

One Czech unnamed medium whose readers boast about their intelligence

One could think it cannot get worse. “Emotions of mother shape child’s behavior.” Of course, no science, peer-reviewed articles, just some psychiatrist invented something.

They write something so general, yet they gain some insight into thing which gains some truth, trying to invent something, but they reinvented the wheel and saying little. If I were an editor, I would have fired the journalist in a matter of seconds.

But wait a second! What is an average IQ of the medium? 105? Maybe. And don’t forget the psychologist’s truthful insight. I said that as a potential editor, the journalist would be short-lived, but what about readers? Nothing, they are content, never challenged the stupidity of these newspapers and media.

However, they boast by their high IQs in the discussion, yet they are nothing but a bunch of uneducated folks of uneducated folks and people not intelligent in some broader sense or generalizable way.

The funniest part is that they believe IQ is exact science while they blame people for not being able to get a job – IQ is heritable and made by the environment. Really a product of stratospheric intelligence.

But the quite calming thing is that those who are really intelligent avoid such discussions, therfore leave those “high-IQs” alone.

They have presale tickets, but why offer it when their readers are so intelligent that they have their ways to obtain it in some other way?

What is the content? Holiday trips, shopping discounts, health myths, tips for saving money, cuisine, comparing loans, how to save money, relationships, kids, entertainment. It cannot get worse.

Their writing style

Media targeting average-intelligence readers avoid long and complex paragraphs. They use short blocks of text, often with headlines breaking every few lines. Readers do not need to scroll through walls of content. Everything is chunked and predictable.

Style stays casual. Writers do not expect background knowledge. They choose simple metaphors. They add emotion. The message is clear even to those who only skim. The structure repeats, reinforces, and simplifies.

Sentences rely on black-and-white frames. Either-or logic dominates. Causes lead directly to effects. Complex conditions vanish. Nuance disappears.

Headlines turn dramatic. They trigger curiosity. They often exaggerate. “You won’t believe this…” works better than logic. Surprise sells. So does fear.

Visuals replace arguments. Charts lack depth but look scientific. Faces cry or smile. Images replace explanation. Emotion moves faster than thought.

Writers address the reader directly. They say “you,” not “people.” They pull you in. The story is personal even when the topic is not. It is always “what this means for your life.”

Repetition is constant. Key points repeat. Sentences circle back. Paragraphs summarize what was just said.

Appeals to identity shape the message. “We Czechs think…” or “Mothers know…” draws the reader closer. Shared assumptions do the work.

Complexity fades. You will not find historical context unless it fits a nostalgic memory. No long arguments. No unresolved contradictions. Just a tidy package.

The article ends the way it starts. It tells you what to think. It reminds you how to feel. And it leaves you with nothing open.

If an average IQ was really 140

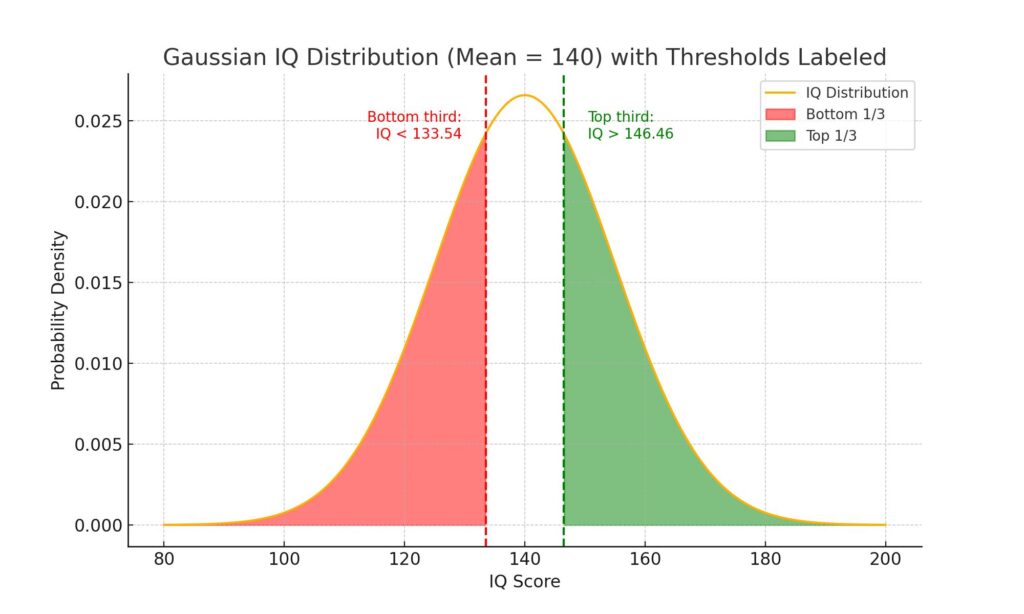

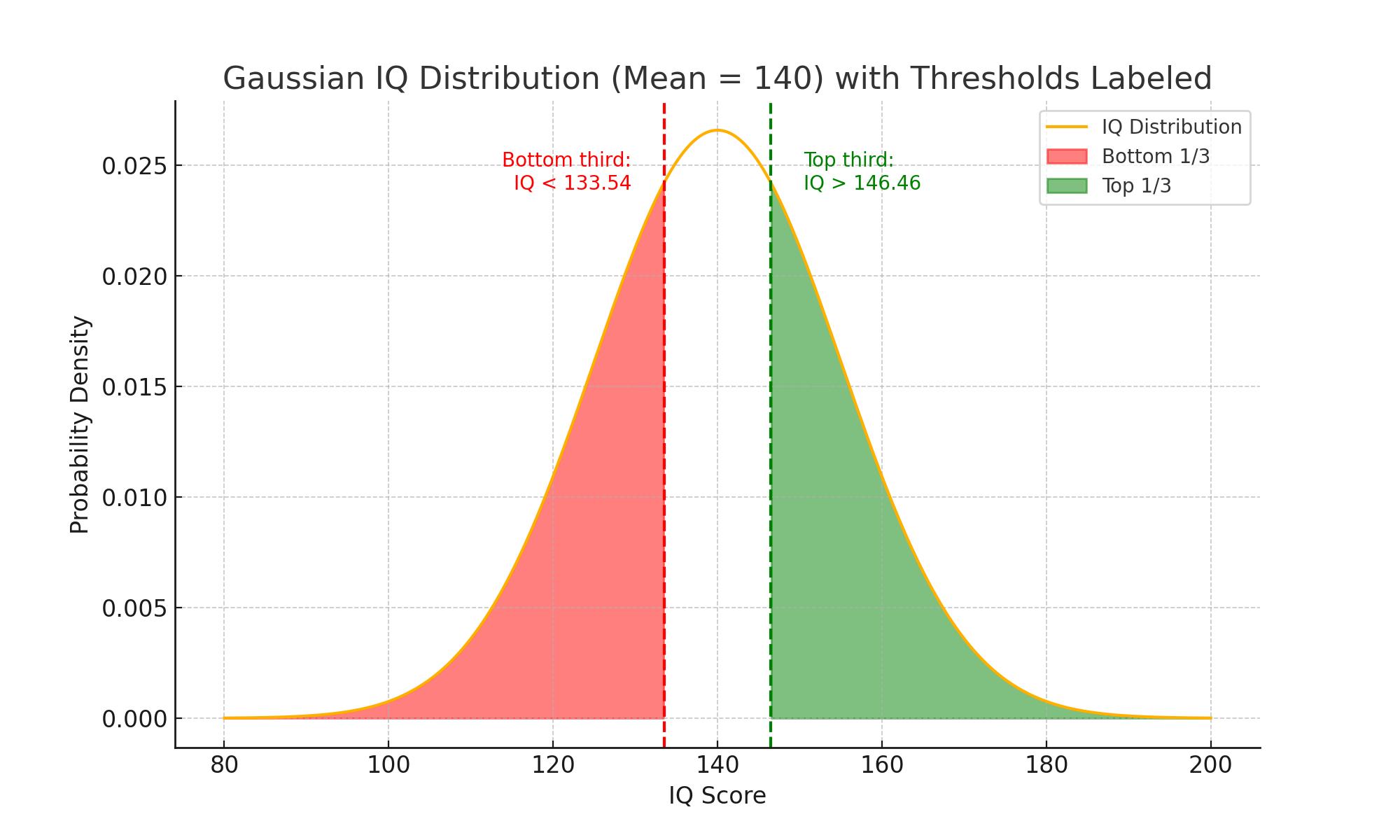

Of course, psychometrics isn’t something exact. If it were hiring for any profession would only be connected with respective IQ. But let’s say we have a huge population (in some developed country) whose average IQ is 140.

Media for people with IQ of 140. What it would look like?

It would be kind of a learning machine. One of the assets of being intelligent is remembering things, then add something newly learned and then make deductions.

Not just some would-be advice about health but something proven by peer-reviewed papers.

Media for IQ 140 would also forced reality upon its supersmart readers: there is no free will, our morality system is deeply flawed and should be changed, there is no deistic and theistic God.

People would be aware that watching TV is just relitct of our prehistoricy instincs.

One Czech economic magazine definitely wanted to change your belief to adhere their, but since people reading was smart they wrote tons of contradicting opinions. Readers were just too smart.

Analytic philosophy

They could learn how to formalize natural language arguments into symbolic logic and spot hidden fallacies in everyday reasoning. Articles could teach them predicate logic, modal operators, and truth-functional schemata—not as abstract symbols, but as tools to analyze political claims, scientific arguments, or legal statements. They would be able to translate messy speech into clean logic and test its validity; they could also compare the expressive power of first-order vs second-order logic, seeing how different logical systems affect the structure of philosophical problems.

They could also study analytic metaphysics, such as the debate over whether abstract objects like numbers, properties, and possible worlds exist. Articles could dive into David Lewis’s modal realism, contrasting it with actualist theories and grounding problems. The focus would be on precision—explaining how metaphysical positions differ not in slogans, but in the formal commitments they require. Readers could learn how to spot ontological inflation, distinguish necessity de dicto vs de re, and explore issues like grounding, supervenience, and identity over time.

Finally, they could explore epistemology and the theory of reference, studying how names refer to objects in the world, and how knowledge claims are justified. Articles could explain Kripke’s causal theory of names, Putnam’s Twin Earth thought experiment, and the Gettier problem in a way that allows readers to reconstruct the arguments step by step. They would not only know the positions, but learn to rebuild them from logical principles, test them with counterexamples, and form their own conclusions with clarity. This level of analysis would not assume philosophical background—it would assume high reasoning ability and the desire to master abstract distinctions through rigor.

Law without free will

While we don’t possess anything like free will, we cannot get murderer let go because he is a sociopath. So instead of thousand fairly tales about morality claims which are meant to distract from financial crimies, there would be cases what a judge should do when confronted with such a case.

IQ 140? Knowing are prehistoric instints

They were carved in the savannah. Shaped by fear, hunger, rivalry, and reproduction. Back then, your survival depended on staying close to the tribe. A bigger village meant more eyes against predators, more hands to gather food, more allies in conflict. It also meant more mating opportunities. That is why your brain lights up when you enter a city. It sees safety, it sees genes spreading. And it does not see bureaucracy, traffic, or pollution. It sees a chance to live.

Yet the reality is different. You are anonymous, you are replaceable. You are safer, yes—but lonelier. Your mind evolved for groups of a hundred. Not millions. That huge crowd overwhelms your ancestral mechanisms. You feel alert. Excited. But also empty. Because those instincts, once perfectly adapted, now misfire.

Another misfire: food. Back then, sweetness meant ripe fruit. Fat meant survival. Salt meant lost electrolytes recovered. Today, we are flooded with sugar, oil, and flavor enhancers. Your mind thinks you have found a hidden treasure. It rewards you for eating. Then punishes you with obesity and chronic illness. You are tricked by your own biology.

Even status works differently. Once, if you were admired by the tribe, you got food, protection, and sex. Now, admiration is digital. You chase numbers—likes, followers, reposts. But your brain reacts as if those were real alliances. They are not. They are illusions. You are rewarded chemically, but not socially. That is why fame never feels enough.

Fear still prevailing

And what about fear? You evolved to detect threats fast. Rustling bushes. Loud noises. Sudden movement. Now, your fear circuits react to headlines. To emails. to texts from your boss. To flashing notifications. Even when nothing truly threatens your life, your system stays on alert. Anxiety becomes a permanent condition. Your amygdala never rests.

Scarcity also shaped you. If you found water, you drank. If you found shelter, you stayed; if you found an opportunity, you took it. There was no tomorrow. But modern life asks for patience. Discipline. Long-term planning. That is why savings are hard, that is why quitting is easy. That is why addiction thrives.

We did not evolve for this comfort. Or for this noise. Or for this abundance. We evolved to solve concrete problems—predators, hunger, storms, injury, exile. We still carry those tools. They just do not match the challenges of today. So they break. Or worse—they harm us. We crave stimulation, but find exhaustion. We chase meaning, but fall into algorithms.

This mismatch defines the modern world. We are animals lost in a maze of our own making. We build cities that our ancestors would worship. But we do not thrive in them. We scroll, panic, consume, compete. And wonder why we feel empty.

Because our instincts are too old. And the world has changed too fast.

Magazine: World through lens of peer-reviewed articles

Let us leave opinions behind. A real magazine for high intelligence must not rely on gut feeling, social consensus, or emotionally loaded phrases. It must point directly to where the data lives—inside peer-reviewed studies. Not just summaries. Not cherry-picked lines. But actual structured results, complete with sample sizes, methods, contradictions, and margins of error.

This section must appear in every issue. A gateway into the research itself. No interpretations added unless they clarify the original findings. If the article explores morality, it links to primary work from moral psychology, evolutionary game theory, and experimental ethics. If the topic is inequality, it cites income distribution curves, cross-country comparisons, and long-term cohort studies.

Readers must be taught to read tables. To follow a regression. To understand p-values without mystification. The goal is not to replace experts—it is to decode them. Articles should walk readers through a single paper: its core question, its framing, its blind spots. Then compare it with a rival study. The contradictions are welcome. High IQ readers do not need coherence. They need access.

The magazine must also include links to original sources—not filtered “science communication,” but the real thing. Abstracts, PDF links, datasets if available. Reading science should not be rare. It should be routine. Because when intelligent people read the data themselves, their thinking shifts. Not because of bias—but because of evidence.

This is the only way to restore intellectual honesty. You do not ask readers to “trust the science.” You show them where it lives. You guide them into it. You help them extract the value. No excuses, no simplifications. And no paternalism. Just the work, in full daylight. Let the data do the talking—if your mind is ready to listen.

How to solve politics

People shoud be aware and taught what acually politics is, that these are background deals no one knows about. They argue on the TV meanwhile the deal was already done. So what what should an average reader with an IQ of 140 know?

IQ 140: How would such party leaders would look like

A legislative assembly? Only super-moral, highly intelligent people with analytical skills and great talent for politics would be allowed. We cannot eradicate politics as a craft (if I exclude some genetical engineering).

Take a look at the average member of the assembly: only the 98th percentile on the common morality Gaussian curve. Intelligence – IQ 145+ (99.8650032777% or 1 in 741), political skills on the 98th percentile. So such a member is pretty rare in the common population. He or she is highly educated on how politics looks in the background, theory and practice.

And now the government? Political skills – 99th percentile, managerial skills 99.96th percentile and morally 98th percentile.

Can you imagine the outcome? Super-rich, equal country where everything is transparent and people don’t need a Supreme Court, or constitution because everything relies on citizens.

Magazine: IQ of 105 and solving politics?

It would be the same as it is now. No 5 IQ points for the better.

But imagine if all the show for the less intelectually able were shown, would something be changed?

No, it wouldn’t be. If every single medium bombarded the readers with how much Big Banks illegally amassed profit, how the super-rich families manipulate POTUS, how the whole patron-client system works.

Having IQ of 140, there would be revolution. An IQ of 105, nothing would happen.

Editorial voice rooted in clarity, not authority

Most publications still cling to hierarchy. They quote professors, prize-winners, think-tank elites—as if intelligence could be borrowed through citation. But this is not how true understanding works. In a magazine aimed at people with an IQ of 140, the source of a claim should never matter more than the structure of the argument itself. Authority is not proof. Prestige is not clarity. A clear argument stands even when no famous name supports it. A weak argument collapses even if every credential in the world is printed beside it.

That is why the editorial voice must operate on entirely different principles. It must cut through fog. It must ask—what does this claim mean, where does it lead, how is it supported? There is no room for inflated language or rhetorical dressing. A writer must not be persuasive through charm or reputation, but through steps. Through precision. Through logical architecture. The reader must always be able to reconstruct the chain from premise to conclusion. If a concept is hard, the writing must slow down. If the idea is controversial, the logic must be even cleaner. No tricks, no emotional nudges, no vague appeals to common sense or expert consensus.

The readers are capable of judging ideas on their own. So the magazine must trust them. It must not say, “Einstein believed” or “Oxford study shows” without showing exactly what and why. It must present the argument in its full shape, with every critical assumption visible. What matters is not who said it, but whether it can be said again—clearly, publicly, and with all reasoning open to attack. Only then can real thinking begin.

Assumes abstract and counterintuitive thinking

High intelligence does not mean knowing more facts. It means handling ideas that are strange, abstract, and often deeply unnatural. The modern world was built by such thinking—by logic that feels wrong, by mathematics that bends intuition, by decisions that defy emotion. A magazine for highly intelligent readers must treat this not as a feature but as a foundation. It must explore paradoxes not for curiosity, but for training. It must introduce Gödelian self-reference, Russell’s paradox, decision-theoretic loops, and moral dilemmas where no answer feels clean. Not to impress. But to push.

Readers should be confronted with ideas like infinite regress, counterfactuals, uncertainty in logic, and the limits of what any system can know about itself. They must wrestle with ideas that make the mind sweat: how a system can be true but unprovable, how rational choices can lead to worse outcomes for everyone, how utility-maximizing actions can break under real-world psychology. No simplification. No comfort. Just the hard truth: our minds evolved for tribal politics and meat-sharing, not for Bayesian calibration or abstract formalism. And yet we must learn it.

That is the task: not to confirm instincts, but to expose them. A reader must see where reason breaks down. Where gut feeling leads astray. Where logic contradicts itself if stretched too far. The magazine must teach readers to think probabilistically, recursively, structurally. To see moral problems in terms of game theory. To understand when definitions are not clear enough to ground an argument. To admit that intuition, though biologically useful, is often the first casualty of rigorous thought. It is only through this lens—of counterintuitive precision—that higher intelligence can be put to work. Not in dominating others. Not in signaling superiority. But in mapping the boundaries of knowledge itself.

Cognitive reflection emphasis

This magazine must challenge not only what readers know—but how they know it. Every issue should contain self-reflective exercises. Mental traps, illusions, and epistemic distortions must be uncovered layer by layer. Readers must confront their own errors. The goal is not to feed information. It is to sharpen cognition. Each article should expose a hidden bias, demonstrate how it works in the brain, and offer a method to neutralize it.

Reflection must be more than abstract. It must be internalized. Am I overconfident? Am I mistaking fluency for truth? Am I rejecting a claim because it feels wrong—or because it actually is? These are not casual questions. They are essential tools. Because a high-IQ mind is not immune to bias. It simply makes more complex mistakes. The magazine must train readers to catch themselves mid-thought. Before the error becomes a worldview.

Highlights unknowns and contradictions

Most media present conclusions. This one must present doubt. It must go where models collapse. Where experts split. Where logic outpaces the facts. Readers do not need certainty. They need clarity about uncertainty. Each field—ethics, epistemology, metaphysics—has points where agreement vanishes. The magazine should focus precisely there.

No pretending the map is complete. Instead, show where knowledge ends. Why theories fail to generalize. Why solutions work under some axioms—but not others. Readers should leave the article not just informed—but disoriented in a precise way. Not confused, but aware of complexity. That is where thinking begins. That is where original reasoning forms.

Cognitive fallacies explored deeply

Most people learn what the fallacy is. Few understand why it exists. This magazine must dig deeper. It must link fallacies to the architecture of the brain. Why do we double down when proven wrong? Why do we see patterns where none exist? Why do tribes feel truer than data? These are not logical defects. They are evolutionary features.

Back then, a fast but wrong decision could save your life. Today, it ruins your judgment. The magazine must show that fallacies are not academic errors. They are ancient mental shortcuts that no longer serve us. Each issue should expose one, trace its origin, and then teach the reader how to override it. Not in theory—in daily thought. The result? A mind that resists its own instincts when the cost of instinct is too high.

Theory of mind at high resolution

High intelligence comes with trade-offs. One of them is self-distortion. Many smart individuals build recursive models of themselves. They simulate others. They simulate how others simulate them. At some point, the map overtakes the territory. That is where alienation begins.

This magazine must explore the risks. How higher IQ often leads to social miscalibration. How assumptions about others collapse under overthinking. How too much abstraction creates loneliness. But also—how to rebuild understanding. How to translate thought into empathy. How to restore communication between different cognitive styles.

Readers must realize that intelligence is not just strength. It is also a liability. Especially when it blinds them to what simpler minds see more clearly. The solution is not to suppress intelligence—but to steer it. Carefully. With reflection, strategy, and humility.

Analytical detachment

Emotion must not drive philosophy. It clouds clarity, it rushes conclusions, it bends logic toward comfort. A magazine for high-intelligence readers must not amplify emotion. It must contain it. Not deny its existence—but hold it at arm’s length. Anger, fear, guilt, hope—each deserves recognition. But never authority.

This magazine must treat emotion the way surgeons treat blood. Part of the process—but not the focus. Articles should dissect the most difficult topics imaginable—suffering, mass death, injustice, cosmic insignificance—and do so with total steadiness. No outbursts, no editorial sighs. No rhetorical spikes. The reader should feel that the writer did not flinch.

Why? Because the real skill is not just thinking. It is thinking while others panic. It is following an argument into dark territory and not retreating. Analytical detachment means holding two things at once: emotional awareness and logical integrity. The feelings are there. But they do not make the decision.

Readers must be trained to pause before outrage. To examine sadness. To reflect before agreeing with their gut. This detachment is not coldness. It is strength. In a world where attention is manipulated, where emotion is monetized, detachment becomes a form of rebellion. A declaration that ideas matter more than instinct.

True intelligence demands this separation. Not because emotion is bad—but because reasoning collapses if it leads. The magazine must model how to hold structure while emotions crash into it. Not by disengaging. But by keeping the structure upright long enough to outlast the wave.

Error as knowledge

Mistakes must not be erased. They must be featured. Because failure is not the enemy of thought—it is its fertilizer. A magazine for advanced readers should treat wrong ideas as valuable intellectual data. Not because they feel interesting. But because they show where the system breaks.

Each issue should include ideas that failed. Predictions that did not hold. Arguments that unraveled under scrutiny. Not to mock the thinker—but to highlight the terrain. Readers must see the line where good reasoning collapses. That line matters more than a thousand correct slogans.

This is how deep minds grow. They do not chase only what works. They study what does not. Because every failed theory asks a new question. Every broken prediction demands a better frame. Sometimes the insight is not in the solution—but in the angle of the failure. Why did it seem right? What blind spot did it expose? What assumption went unnoticed?

Articles must walk through this process. Clearly. Without shame. Without softening. Readers should not be told “this model failed.” They should be shown—why it looked correct, where it went wrong, and how the failure could be used. This is not error as weakness. It is error as illumination.

And at the end—no resolution. No final answer. Just tension. Because the most intelligent minds learn to live with uncertainty. They know that not every question ends cleanly. Some articles should stop mid-thought, mid-conflict, mid-collapse. That is the moment when intelligence starts working—not by finishing—but by holding the unresolved in view, and continuing anyway.

From stupidity to real scientific fields

Cognitive psychology, evolutionary psychology, behavioral economics, neuropsychology, decision theory, moral psychology, social neuroscience, computational neuroscience, metacognition research, developmental psychology, psychometrics, attention and memory research, abnormal psychology, psychopathology, learning theory, complex systems theory, chaos theory, nonlinear dynamics, fractal analysis, information theory, systems biology, mathematical biology, neuroeconomics, linguistic typology, syntax and formal grammar, computational linguistics, philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, logic and set theory, modal logic, metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of science.

Bayesian epistemology, cognitive anthropology, sociobiology, behavioral genetics, anthropology of religion, historical psychology, memetics, biosemiotics, artificial life, consciousness studies, affective neuroscience, cybernetics, network theory, statistical modeling of cognition, behavioral game theory, dual-process theory, evolutionary game theory, agent-based modeling, population dynamics, human ecology, biocultural evolution, brain-computer interfaces, neurophilosophy, mathematical modeling of behavior, pattern recognition theory, theory of computation and cognition, evolutionary psychiatry, prediction error theory, reinforcement learning models in humans, embodied cognition, perception-action coupling, mental time travel, self-representation research, cognitive load theory, IQ-environment interaction studies, self-deception models, brain signal entropy studies, socio-cognitive conflict theory.

IQ 140 and magazines: Conclusion

Welcome back to reality. The average IQ is 105. So what you get is exactly what that number allows. Scandals appear, scandals disappear. One politician falls, another rises. The topics change every week, but the stupidity stays. You cannot expect strict logic in a society where most minds cannot even trace cause and effect across three steps.

Stupid content is not a glitch. It is design. It matches the audience. Media write for the feeble-minded. And the journalists? Most of them cannot produce high-quality writing because they were never trained for it—and were never smart enough to seek that training. No logic, no internal consistency. No long-form structure. Just fragments, emotions, and clichés.

The result is predictable. One meaningless article after another. One illusion reinforced, then another. A parade of shallow outrage, fake dilemmas, moral preaching, and zero intellectual challenge. The rare reader who actually thinks quits early. The rest are perfectly satisfied because they never notice the emptiness.

A magazine for people with IQ 140 cannot resemble this. It must be the opposite. No fake controversies. No rewriting of old myths, no dumbing down. Just ideas with sharp edges. Content that feels difficult, uncomfortable, even unfriendly—because that is what honest thinking looks like. Real philosophy, real structure. Real reflection.

This is not elitism. This is survival. A society without a space for its most intelligent minds will lose them. If they are not challenged, they will turn inward. Or worse, they will leave public life altogether. But if a medium exists for them—cold, clear, exact—they might come back. Quietly. Thoughtfully. But decisively.

Because the world will not be fixed by emotions or symbols. Only by people who still know how to think when everyone else forgot how.

Leave a Reply